KUZEY KIBRIS’TA AZINLIK HAKLARI

Ali DAYIOĞLU

Bu yazıda derlenen metinde kullanılan terminoloji Avrupa Birliği (AB) tarafından desteklenen projelerden biri olan “Kıbrıs’ın Kuzeyinde İnsan Haklarının

Haritalandırılması Projesi” kapsamında Kıbrıslı Türk İnsan Hakları Vakfı ve yazarların sorumluluğu altındadır. Bu yayının içeriği hiçbir şekilde Avrupa

Komisyonuna atfedilemez. AB, üyesi olarak sadece Kıbrıs Cumhuriyeti’ni tanır, “Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti”ni tanımaz. 389/2006 sayılı Konsey

Tüzüğünün 1(3) maddesine göre “bu katkının sağlanması bu bölgelerde Kıbrıs Cumhuriyeti dışındaki kamu otoritesini tanıma anlamını taşımaz”.

The texts compiled in this publication including the terminology used lay in the sole responsibility of the author(s) and/or the Turkish Cypriot Human

Rights Foundation as one of the beneficiaries of the EU funded project “Mapping Human Rights in the Northern Part of Cyprus”. In no way can the

content of this publication be attributed to the European Commission. The EU does not recognise the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” but only

the Republic of Cyprus as its member state. According to article 1(3) of Council Regulation 389/2006 “the granting of such assistance shall not imply

recognition of any public authority in the areas other than the Government of the Republic of Cyprus”.

KUZEY KIBRIS’TA AZINLIK HAKLARI

Ali DAYIOĞLU

KIBRISLI TÜRK İNSAN HAKLARI VAKFI YAYINLARI NO: 1

1. Baskı - Mayıs 2012

Lefkoşa - Kıbrıs

ISBN: 978-9963-719-10-5

Tanzimat Sokak No: 176 Lefkoşa

0533 869 75 42

KAPAK ve GRAFİK TASARIM

Erdoğan Uzunahmet

SAYFA DÜZENLEME

Erdoğan Uzunahmet

BASKI

MAVİ BASIM

Esnaf ve Zanaatkârlar Sitesi - Lefkoşa

Tel: 0533 8631957

İLETİŞİM

KIBRISLI TÜRK İNSAN HAKLARI VAKFI

www.ktihv.org

e-mail: info@ktihv.org

Haşmet Gürkan Sok. No: 3 - Lefkoşa-Kıbrıs.

Tel: +90 392 229 17 48 / 49

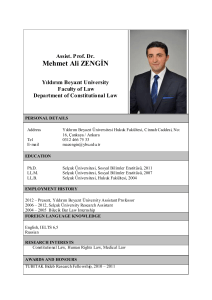

ALİ DAYIOĞLU, 1970 yılında Limasol’da doğdu. Türk Maarif Koleji’nden sonra

1992’de Ankara Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi’ni bitirdi. Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal

Bilimler Enstitüsü Uluslararası İlişkiler Ana Bilim Dalı’nda 1996’da yüksek lisans,

2002’de de doktora programını tamamladı. 1997-2000 döneminde ve 2002’den bugüne Yakın Doğu Üniversitesi Uluslararası İlişkiler Bölümü’nde milliyetçilik, insan ve

azınlık hakları ile Türk dış politikası konularında dersler verdi. Bu konularla ilgili çeşitli dergi ve gazetelerde yayınlanmış makaleleri ile Toplama Kampından Meclis’e:

Bulgaristan’da Türk ve Müslüman Azınlığı (İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 2005, 512 sayfa) isimli bir kitabı vardır.

e-mail: dayioglu@kktc.net ; aldayfen@hotmail.com ; adayioglu@neu.edu.tr

Kıbrıslı Türk İnsan Hakları Vakfı (KTİHV), Avrupa Birliği tarafından Kıbrıslı

Türklere ayrılan mali yardım kapsamında finanse edilip toplam 2 yıldan fazla süren

Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta İnsan Haklarının Haritalandırılması Projesi’ni tamamlamıştır. Proje

kapsamında insan haklarıyla ilgili 11 konuda (Azınlık Hakları; Çocuk Hakları; Tutuklu

Hakları; Cinsel İstismar Amacıyla İnsan Ticareti; Göçmen İşçilerin İnsan Hakları; Mülkiyet

Hakları; Kadının İnsan Hakları; Engelli Kişilerin Hakları; Mülteci Hakları; Lezbiyen, Gey,

Biseksüel, Transgender Kişilerin Hakları; Kayıp Kişiler ve Ailelerinin İnsan Hakları)

raporlar yazılmıştır. Söz konusu raporlar, Kuzey Kıbrıs’taki insan haklarının durumunun

ayrıntılı ve tarafsız bir ‘harita’sını çıkarıp bu konudaki düzeyin uluslararası insan haklar

standartları seviyesine çıkarılmasına katkıda bulunmayı amaçlamaktadır. Türkçe ve

İngilizce olarak hazırlanmış raporlar kamuoyu ve ilgili tüm paydaşlarla paylaşılacaktır.

Ülkemizde insan haklarının daha ileri boyuta taşınmasında önemli bir araç olacağına

inandığımız projemize katkıda bulunanlara teşekkürü borç biliriz:

EROL AKDAĞ, MUSTAFA ABİTOĞLU, GÖZDE ÇEKER, FİKRİYE ERKANAT SAKALLI, UMUT

ÖZKALELİ, MELİKE BİSİKLETÇİLER, AYCAN AKÇIN, BAHAR AKTUNA, RAHME VEZİROĞLU,

İSMAİL BAYRAMOĞLU, LEYLA FALHAN, GÖRKEM REİS, FEZİLE OSUM.

EMİNE ÇOLAK, VEYSEL EŞSİZ, FATMA GÜVEN LİSANİLER, ILGIN YÖRÜKOĞLU, MEHVEŞ

BEYİDOĞLU, ÖMÜR YILMAZ, MEHMET ERDOĞAN, SEVİNÇ İNSAY, UTKU BEYAZIT, OLGA

DEMETRIOU, REBECCA BRYANT HATAY, TUFAN ERHÜRMAN, DOĞUŞ DERYA, TEGİYE

BİREY, ŞEFİKA DURDURAN, UMUT BOZKURT, ERDOĞAN UZUNAHMET, HÜRREM

TULGA, İLKER GÜRESUN.

DERVİŞ UZUNER, PERÇEM ARMAN, HAZAL YOLGA, ÖMÜR BORAN, FATMA TUNA, ÇİM

SEROYDAŞ, ORNELLA SPADOLA, ENVER ETHEMER, ASLI GÖNENÇ, DİLEK ÖNCÜL, GAVIN

DENSTON, FATMA DEMİRER, FAİKA DENİZ PAŞA, ÖNCEL POLİLİ, CEREN GÖYNÜKLÜ, ALİ

DAYIOĞLU, SELEN YILMAZ, CEREN ETÇİ, CEMRE İPÇİLER, ZİLİHA ULUBOY, HOMOFOBİYE

KARŞI İNİSİYATİF DERNEĞİ.

Canan Öztoprak

Proje Koordinatörü

Kıbrıslı Türk İnsan Hakları Vakfı

KUZEY KIBRIS’TA AZINLIK HAKLARI

Ali DAYIOĞLU

İÇİNDEKİLER

ENGLISH •71

GİRİŞ:

AZINLIK KAVRAMI VE TANIMI •9

BİRİNCİ BÖLÜM:

ULUSLARARASI HUKUKTA AZINLIK HAKLARI •13

I) Birleşmiş Milletler Örgütü ve Azınlıkların Korunması •13

A) Kurulduğu Dönemde BM Örgütünün Azınlıklar Konusuna Yaklaşımı •13

B) BM Örgütünün Azınlıklar Konusundaki Bakışının Değişmesi ve Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar

Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin 27. Maddesi •13

C) Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Yönünde Kabul Edilen Belgeler •15

D) Ulusal ya da Etnik, Dinsel ve Dilsel Azınlıklara Mensup Kişilerin Haklarına İlişkin Bildirge •16

II) Bölgesel Örgütlenmeler •17

A) Avrupa Konseyi ve Azınlıkların Korunması •17

1) Avrupa İnsan Hakları Sözleşmesi •17

2) Bölgesel Diller ya da Azınlık Dilleri Avrupa Şartı •18

3) Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve Sözleşme ve Uygulanması •19

B) Avrupa Birliği ve Azınlıkların Korunması •20

C) Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Konferansı / Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Teşkilatı Belgelerinde Azınlık

Haklarının Korunması •21

İKİNCİ BÖLÜM:

KUZEY KIBRIS’TA AZINLIKLARLA İLGİLİ MEVZUAT VE UYGULAMALAR •25

I) Azınlıklarla İlgili İç Hukuk Düzenlemeleri ve Kabul Edilen Uluslararası Belgeler •25

II) Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta Azınlıklarla İlgili Uygulamalar •27

A) Hıristiyan Azınlıklar •27

1) Rumlar •27

a) Eğitim Konusundaki Uygulamalar •29

b) Din ve Vicdan Özgürlüğü Konusundaki Uygulamalar •35

c) Ekonomiyle İlgili Konular •42

d) Diğer Hak ve Özgürlüklerle İlgili Uygulamalar •44

2) Marunîler •47

a) Eğitim Konusundaki Uygulamalar •50

b) Din ve Vicdan Özgürlüğü Konusundaki Uygulamalar •50

c) Ekonomiyle İlgili Konular •51

d) Siyasal Hak ve Özgürlükler Konusundaki Uygulamalar •53

B) Hıristiyan Olmayan Azınlıklar •55

1) Romanlar •55

2) Aleviler •57

3) Kürtler •59

SONUÇ •61

KAYNAKÇA •65

7

GİRİŞ:

AZINLIK KAVRAMI VE TANIMI

Azınlık, kavram olarak, “belli bir topluluk içinde farklılıklar gösteren ve başat olmayan gruba verilen isimdir”.1 Tarihin her döneminde çoğunluktan farklı özellikler gösteren daha

küçük toplulukların var olduğu varsayımından hareketle, azınlık olgusuna insanların toplum

halinde yaşamaya başladıkları andan itibaren rastlandığını söylemek mümkündür. Buna karşılık, azınlık kavramı Reform Hareketinin ve mutlakıyetçi krallıkların belirdiği 16. yüzyılda, yani

azınlıkların korunmasının gündeme geldiği dönemde ortaya çıkmıştır.

Kavram olarak bu kadar eski olmasına rağmen, bugüne kadar tüm kesimlerin üzerinde

oydaşmaya vardıkları bir azınlık tanımı oluşturulabilmiş değildir. Bunun iki temel nedeni vardır: 1) Azınlık kavramının salt hukuksal değil, çok çeşitli görünümleri bulunan ve farklı çıkarları

ilgilendiren sosyopolitik bir kavram olması;2 2) Ulusal bütünlük endişesiyle devletlerin bu konuda hukuki bir tanımla kendilerini bağlamaktan çekinmeleri.3

Karmaşık bir nitelik gösteren azınlık kavramı sosyolojik ve hukuksal bakımlardan ele

alınarak tanımlanmaya çalışılmaktadır. Sosyolojik bakımdan “bir toplulukta sayısal bakımdan

azınlık oluşturan, başat olmayan ve çoğunluktan farklı niteliklere sahip olan grup” şeklinde

tanımlanabilecek olan azınlık kavramı bu açıdan genelde “ezilmiş” olmayı içermektedir. Buna

göre eşcinseller, resmî çevreler ve toplumun geneli tarafından kabul edilmeyen dinsel inançlara sahip bulunanlar, uyuşturucu bağımlıları, evsizler, hatta kadınlar birer azınlıktır.4

Azınlık kavramının hukuksal bakımdan tanımlanması konusunda tüm durumları kapsayan ve bütün devletlerce kabul edilen bir tanımın bugüne kadar yapılamamasına rağmen,5

azınlıklarla ilgili çeşitli uluslararası belgelerde azınlık kavramını tanımlamada birbirine benzer

ölçütlerin kullanılması bazı tanımları ortaya çıkarmıştır.6

Bunların en önemlisi Birleşmiş Milletler (BM) Ayrımcılığın Önlenmesi ve Azınlıkların

Korunması Alt Komisyonu Özel Raportörü Francesco Capotorti’nin 1976’da yürürlüğe giren

BM “Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin” azınlıkların korunmasına ilişkin 27.

maddesi bağlamında bu maddenin uygulama alanını belirlemek amacıyla hazırladığı incelemede 1978’de yaptığı tanımdır. Sonraki tanım denemelerinin temel çerçevesini oluşturan tanımda Capotorti azınlığı şu şekilde tarif etmiştir:

1. Oran, Baskın, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, 4. B., Ankara, İmaj Yayıncılık, 2001, s. 66.

2. Oran, Baskın Türk-Yunan İlişkilerinde Batı Trakya Sorunu, 2. B., Ankara, Bilgi Yayınevi, 1991, s. 39-40.

3. Çavuşoğlu, Naz, Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukukunda Azınlık Hakları, İstanbul, Bilim Yayınları, 1999, s. 24;

Çavuşoğlu, Naz “‘Azınlık’ Nedir?” İnsan Hakları Yıllığı, C. XIX-XX, (1997-1998), s. 101.

4. Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 67; Üstel, Füsun, “Ulusal Devlet ve Etnik Azınlıklar”, Birikim, No. 73, (Mayıs

1995), s. 13.

5. Bundan dolayı günümüzde, Uluslararası Sürekli Adalet Divanının (USAD) belirli bir dönemde belli antlaşmaların

yorumu amacıyla yaptığı çeşitli azınlık tanımları dışında uygulanan uluslararası hukukta kabul edilmiş herhangi bir

azınlık tanımı söz konusu değildir. Pazarcı, Hüseyin, Uluslararası Hukuk Dersleri, C. II, 5. B., Ankara, Turhan Kitabevi,

1998, s. 185.

6. Söz konusu tanımlar için bkz. Dayıoğlu, Ali, Toplama Kampından Meclis’e: Bulgaristan’da Türk ve Müslüman

Azınlığı, İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 2005, s. 24-26.

9

10

“Başat olmayan bir durumda olup, bir devletin geri kalan nüfusundan sayısal olarak daha az

olan, bu devletin uyruğu olan üyeleri etnik, dinsel ve dilsel nitelikler bakımından nüfusun geri

kalan bölümünden farklılık gösteren ve açık olarak olmasa bile kendi kültürünü, geleneklerini

ve dilini korumaya yönelik bir dayanışma duygusu taşıyan bir gruptur.”7

Öğretide büyük ölçüde paylaşılan Capotorti’ninki başta olmak üzere, dikkate alınan

diğer tanımlar incelendiğinde8 bunların dördü objektif, biri de sübjektif olmak üzere beş temel

ölçüte dayandıkları görülmektedir. Buna göre, bir azınlık grubunun varlığından söz edebilmek

için gerekli olan ilk ölçüt, bir devletin nüfusunun geri kalanından farklı etnik, dinsel ya da dilsel

özellikler taşıyan bir grubun varlığıdır.9 Burada bir yandan kimin hangi ırktan olduğunu belirlemenin, diğer yandan da ırk kavramını bilimsel olarak incelemenin güçlüğünden dolayı, ırk

kavramı renkleri siyah ve beyaz gibi farklı olan insanların bir arada bulundukları durumlar dışında dikkate alınmayabilir.10 Belirtilmesi gereken ikinci husus, azınlık oluşturan grupların ilgili

devlet tarafından hukuken tanınıp tanınmamalarının önem taşımadığıdır. Bu nedenle konuyla

ilgili uluslararası belgelerde azınlık gruplarının ilgili devlet tarafından tanınmış olması gerektiği

ölçütüne yer verilmediği gibi, bu grupların ilgili devlet tarafından azınlık olarak tanınmaması

da bunların azınlık niteliğini ortadan kaldırmamaktadır.11

7. Capotorti, Francesco, Study on the Rights of Persons Belonging to Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, E/

CN. 4/Sub. 2/384/Rev. 1, New York, United Nations, 1979, para. 568.

8. Azınlık kavramının yanı sıra etnik, dinsel ve dilsel azınlıkların tanımlanmasında da ciddi sorunlar söz konusudur. Bu

konuda özellikle ulusal azınlık-etnik azınlık kavramlarının tanımları arasındaki farka dikkat çekilmekte, ulusal azınlık

kavramının akraba devleti bulunan, etnik azınlık kavramının ise akraba devlete sahip olmayan azınlıkları ifade etmek

için kullanıldığı belirtilmektedir (Üstel, op. cit., s. 13’ten A-L. Sanguin, “Quelles Minorités pour quels territories”, A-L.

Sanguin (der.), Les Minorités Ethniques en Europe, Paris, Editions I’Harmattan, 1993, s. 8-9). Böyle bir ayrıma karşı

çıkan kimi yazarlar ise, ulusal azınlık kavramının bir devletin sınırları içerisinde bulunan ve o devletin vatandaşı olan

etnik, dinsel ya da dilsel azınlıkları kapsayacak şekilde kullanılması gerektiğini belirtmektedirler. Çavuşoğlu, ‘Azınlık’

Nedir?, s. 97’den Eide, Asbjørn, “The Ethnocentrisms and Nationalisms of Today, International Institute of Human

Rights, Twenty Fourth Study Session Collection of Lectures, Strasbourg, 1993, para. 19. Bu tartışmalar için bkz. Çavuşoğlu, Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukukunda Azınlık Hakları,s. 28-29; Çavuşoğlu, ‘Azınlık’ Nedir?, s. 96-97.

Ulusal azınlık kavramının, yukarıda belirtilenlerin dışında, başka iki anlam daha taşıdığı belirtilmektedir. Birinci

anlama göre, ulusal azınlık, azınlık sayılabilmek için gerekli objektif ölçütlerin yanı sıra, sübjektif ölçüte, yani azınlık

bilincine sahip olan grubu ifade etmektedir. Bundan yola çıkılarak azınlık bilinci güçlü olmayan farklı grup “ulusal

azınlık” değil, “kültürel azınlık” sayılmaktadır. Diğer yandan, ulusal azınlık kavramının göçmen işçiler, sığınmacılar

vb. gibi “yeni azınlıklar”ın karşıt kavramı olarak kullanıldığı belirtilmektedir. Bu konudaki tartışmalar için bkz. Oran,

Baskın Türkiye’de Azınlıklar: Kavramlar, Teori, Lozan, İç Mevzuat, İçtihat, Uygulama, 5. B., İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 2008, s. 41-42.

Bir başka görüş ise, ulusal azınlıkları “büyük bir devlet şemsiyesi altında toplanmış ayrı ve potansiyel olarak özyönetimli toplumlar”, etnik grupları da “başka bir topluma girmek üzere ulusal cemaatlerini terk etmiş göçmenler”

şeklinde tanımlamaktadır. Kymlicka, Will, Çokkültürlü Yurttaşlık: Azınlık Haklarının Liberal Teorisi, çev. Abdullah

Yılmaz, İstanbul, Ayrıntı Yayınları, 1998, s. 51.

9. Ancak, bütün etnik, kültürel, dinsel veya dilsel farklılıkların mutlaka ulusal azınlıkların oluşumuna yol açmadığı,

burada sübjektif ölçütün, yani azınlık bilincinin varlığının belirleyici olduğu ifade edilmektedir. Oran, Türkiye’de

Azınlıklar, s. 40.

10. Oran, Türk-Yunan İlişkilerinde Batı Trakya Sorunu, s. 41; Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 67.

11. USAD, verdiği bir danışma görüşünde toplulukların [azınlıkların] varlıklarının hukuki değil, fiili bir durum olduğunu belirtmiştir (Ramaga, Philip Vuciri, “The Group Concept in Minority Protection”, Human Rights Quarterly,

Vol. XV, No. 3, (August 1993), s. 576-577 ve Pejic, Jelena, “Minority Rights in International Law”, Human Rights

Quarterly, Vol. IXX, No. 3, (August 1997), s. 673’ten Advisory Opinion on Greco-Bulgarian “Communities”, P.C.I.J.

Series B, No. 17, 1930). BM İnsan Hakları Komitesi de Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin 27. maddesine ilişkin olarak yaptığı Genel Yorum’da azınlıkların varlıklarının ilgili devletlerin onları tanıyıp tanımamalarına bağlı olmadığını vurgulamıştır (UN Human Rights Committee, “General Comment No. 23 (50) on Article 27/

Minority Rights”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. XV, (1994), s. 235, para. 5.2). Avrupa Konseyi (AK) bünyesinde

hazırlanan ve 1 Şubat 1998’de yürürlüğe giren Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve Sözleşme ise bu

konuda yeni bir tartışmayı beraberinde getirmiştir. Çerçeve Sözleşme’de taraf devletlere Sözleşme’yi ülkelerindeki

kimi bölgelerde uygulamama yetkisinin tanınmasının yanı sıra, azınlık tanımına yer verilmemesinden dolayı bazı

imzacı devletler ülkelerindeki hangi grupların azınlık sayılıp sayılmayacakları konusunda kendilerini yetkili görme

eğiliminde olmuşlardır. Ancak, Danışma Komitesi, Çerçeve Sözleşme’de azınlık tanımının olmamasının devletleri

bu konuda tamamen serbest bırakmadığını bildirmiştir. Komite’nin İtalya hakkında verdiği bu görüşle ilgili olarak

bkz. Kurubaş, Erol Asimilasyondan Tanınmaya: Uluslararası Alanda Azınlık Sorunları ve Avrupa Yaklaşımı, Ankara,

Asil Yayın Dağıtım, 2004, s. 212-213’ten Advisory Committee, Opinion on Italy Adopted on 14 September 2001,

ACFC/INF/OP/1 (2002) 007, para. 13-14.

İkinci ölçüt olarak, etnik, dinsel ya da dilsel özellikleri nedeniyle nüfusun geri kalanından ayrılan grupların çoğunluktan sayıca az olmaları gerekir. Burada çoğunluktan farklı

olan özelliklerini sürdürmek isteyen grubun bunu sağlayacak yeterli sayıya sahip olması önem

taşır. Küçük bir grubun istekleri karşılanacak diye devletin kaynaklarının ölçüsüz bir şekilde

sarf edilmemesi, harcanacak çaba ile elde edilecek yarar arasında bir paralelliğin bulunması

önemlidir. Diğer yandan, azınlık-çoğunluk ilişkisi yerine bir arada yaşamak durumunda olan

topluluklardan söz etmek gerekeceğinden, azınlıkla çoğunluğun nüfus oranlarının birbirine

yakın olmaması gerekmektedir. Son olarak, azınlık grubunun ülkenin kimi bölgelerinde çoğunluğu oluşturması bu grubun azınlık olduğu gerçeğini değiştirmemektedir.12

Üçüncü olarak, azınlığın başat-egemen bir pozisyonda olmaması gerekir. Bu ölçüt

azınlığın sayısal olarak nüfusun geri kalanından daha az olması gerektiği koşulunu tamamlamaktadır. Ülke yönetimini ve ülkenin tüm olanaklarını elinde bulunduran, toplumun geriye kalan kesimine kurumsallaşmış bir ayrımcılık uygulayan ve nüfusun geneline göre sayıca az olan

egemen konumdakilerin değil, ayrımcılığa muhatap kalan nüfusun geriye kalan kesiminin korunması gerekmektedir. Burada egemen olmama ölçütü yalnızca siyasi güç bakımından değil,

ekonomik, kültürel ve sosyal statü bakımından da egemen olmama şeklinde anlaşılmalıdır.13

Dördüncü olarak, azınlık haklarından yararlanacak kişilerin bulundukları ülkenin vatandaşlığına sahip olmaları gerekmektedir. Bu durumda yabancılar, sığınmacılar, uyruksuzlar

azınlık tanımının dışında kalmaktadırlar.14

Bir azınlık grubunun varlığından söz edebilmek için söz konusu dört objektif ölçütün

yanı sıra, bir de sübjektif ölçütün varlığı gereklidir. Buna göre, bir devletin nüfusunun geri kalanından farklı etnik, dinsel ya da dilsel özellikler taşıyan grubun bu farklılıklarını korumayı isteyen bir azınlık bilincine sahip olması gerekir. Aksi takdirde söz konusu grubun asimile olmak

istediği anlaşılır ve bu grup azınlık olarak nitelendirilemez. Sınıf bilinci olmadan sosyal sınıf

olamayacağı gibi, azınlık bilinci olmadan da azınlık olamaz.15 Özellikle 1991 tarihli ulusal azınlıklarla ilgili Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Konferansı (AGİK) Cenevre Uzmanlar Toplantısından

itibaren bir grubun azınlık sayılabilmesi için objektif koşulların tümünün mevcut olmasının

yeterli olmadığı, bu konuda azınlık bilincinin belirleyici bir koşul olarak kabul edildiği görülmektedir.16

Bu genel bilgileri aktardıktan sonra, Kuzey Kıbrıs’taki azınlıkları iki ana grupta sınıflandırabiliriz: 1) Hıristiyanlar; 2) Hıristiyan olmayanlar. Birinci grupta Rumlar ve Marunîler,

ikincisinde ise Romanlar, Aleviler ve Kürtler yer almaktadır.

12. Oran, Türk-Yunan İlişkilerinde Batı Trakya Sorunu, s. 41; Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 67-68.

13. Pejic, op.cit., s. 671.

14. Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 68-69. Bugün azınlıkların korunması konusunda üzerinde en fazla tartışılan

konulardan biri azınlık haklarından vatandaşların dışındaki kişilerin de yararlanıp yararlanamayacaklarıdır. Günümüzde azınlık koruma hükümlerinden yararlanmada vatandaş olma ölçütü halen belirleyiciliğini sürdürmekle birlikte, vatandaş olmayanların da azınlık haklarından yararlanmaları gerektiği yönündeki görüşler gittikçe daha çok

dile getirilmektedir. Bu konudaki tartışmalar için bkz. Dayıoğlu, op.cit., s. 29-30, 22 numaralı dipnot.

15. Oran, Türk-Yunan İlişkilerinde Batı Trakya Sorunu, s. 42; Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 69. Söz konusu

ölçüt bir azınlığa mensup olmada kişisel tercih hakkını kapsamakta olup, bu hak birçok uluslararası belgede düzenlenmiştir. Bununla birlikte, Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve Sözleşme’yi Açıklayıcı Rapor’da kişinin

herhangi bir azınlığa mensup olmayı keyfi olarak tercih etme hakkının bulunmadığı, bu tercihin kişinin kimliği ile

ilgili objektif ölçütlere bağlı olduğu belirtilmiştir. Bkz. “Explanatory Memorandum on the Framework Convention

for the Protection of National Minorities”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. XVI, (1995), s. 103, para. 36. Ayrıca bkz.

Çavuşoğlu, ‘Azınlık’ Nedir?, s. 100.

16. Azınlık bilincinin önemiyle ilgili olarak bkz. Oran, Türkiye’de Azınlıklar, s. 40-41. Buraya kadar anlatılanlarla ilgili

olarak daha geniş bilgi için bkz. Dayıoğlu, op.cit., s. 21-31.

11

12

Görüldüğü gibi burada din temelli bir gruplandırma yapılmıştır. Oysa, yukarıda da değinildiği gibi, azınlıkları belirlemede din, ölçütlerden yalnızca biridir. Bunun dışında etnik ve

dilsel farklılıklar da belirleyici bir özellik taşımaktadır. Durum buyken Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta azınlık

oluşturan grupların Hıristiyanlar ve Hıristiyan olmayanlar şeklinde ele alınması tamamen pratik gerekçelerden dolayıdır. Burada etnik temelli bir sınıflandırma yapılsa, bu açıdan azınlık

oluşturan Rumlar, Marunîler, Romanlar ve Kürtler bir başlık altında ele alınacak, Aleviler ayrı

olarak incelenecekti. Dilsel bir gruplandırma yine aynı sonucu verecekti. Dolayısıyla bölümler arasında ciddi bir dengesizlik olacaktı. Dinsel temelli bir sınıflandırma ise, çoğunluktan

etnik, dinsel ve dilsel farklılıklar gösteren ve çalışmanın ana konusunu oluşturan Rumlarla

Marunîleri, etnik ve dilsel azınlık olan Romanlar ve Kürtler ile dinsel bir azınlık oluşturan Alevilerden daha rahat ayırmamızı ve bölümler arasında denge kurmamızı sağlamaktadır.

Bununla birlikte, bu sınıflandırmanın çok sağlıklı olmadığını da belirtmek gerekmektedir. Nedeni, herhangi bir resmî veri bulunmamakla birlikte, Alevilerin bir kısmının Kürt etnik

kökenli olma ihtimalidir. Böyle bir durum bizi, Alevilerin bir bölümünün ayrıca etnik azınlık

olarak değerlendirilmesi gerektiği sonucuna götürmektedir. Fakat hemen hemen tüm uluslararası raporlarda ve konuyla ilgili yayınlarda etnik kökenlerine bakılmaksızın Alevilerin tümünün aynı başlık altında değerlendirilmesi, bu çalışmada da benzer bir yöntemin izlenmesinde

belirleyici olmuştur.

Bu noktada Alevilerin neden dinî bir azınlık olarak değerlendirildiği sorgulanabilir. İleride ayrıntısıyla değinileceği gibi, her ne kadar Müslümanlığın bir kolu şeklinde değerlendiren

görüşler söz konusuysa da, Aleviliğin Türkiye’de ve Türkiye’deki kadar belirgin olmamakla birlikte Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta devletin hâkim öğreti olarak kabul ettiği Sünni-Hanefilikten büyük ölçüde

farklılık taşıdığı, dolayısıyla Alevilerin bir azınlık grubu oluşturdukları açıktır.17

Son olarak Kıbrıslı Türk yetkililer tarafından Hıristiyanların resmen değil fiilen azınlık olarak değerlendirildiklerini, buna karşılık Hıristiyan olmayanların ne resmen, ne de fiilen

azınlık olarak görüldüklerini söylemek gerekmektedir.

Azınlık kavramı ve tanımıyla ilgili bu açıklamalardan ve Kuzey Kıbrıs’taki azınlık gruplarından kısaca söz ettikten sonra, şimdi uluslararası hukukta azınlık haklarının gelişimini özetleyerek aktarabiliriz. Bu özet, Kuzey Kıbrıs’taki mevzuatta ve uygulamada ne yapılması gerektiğine dair bir fikir verecektir.

17. Bu durum 1922-1923 Lozan Barış Konferansında Türk heyeti adına azınlık konularını müzakere eden Dr. Rıza

Nur’un sözlerinde somutlaşmaktadır. Rıza Nur, Türk heyetinin azınlıkları tanımlamada ırk ve dil ölçütlerinin yanı

sıra din ölçütünü de reddetmesinin nedenini Alevileri azınlık yapmamak, dolayısıyla da uluslararası koruma altına

sokmamak olduğunu belirtmektedir. Rıza Nur şöyle demektedir: “Frenkler bizde ekalliyet diye üç nevi biliyorlar:

Irkça ekaliyet, dilce ekaliyet, dince ekaliyet. Bu bizim için gayet vahim bir şey, büyük bir tehlike… Din tabiri ile Halis

Türk olan iki milyon kızılbaşı da ekalliyet yapacaklar.” Nur, Rıza, Hayatım ve Hatıratım, C. III, İstanbul, Altındağ

Yayınevi, 1967, s. 1044.

BİRİNCİ BÖLÜM:

ULUSLARARASI HUKUKTA AZINLIK HAKLARI

I) Birleşmiş Milletler Örgütü ve Azınlıkların Korunması

A) Kurulduğu Dönemde BM Örgütünün Azınlıklar Konusuna Yaklaşımı

Milletler Cemiyeti (MC) döneminde azınlık konuları insan haklarından ayrı olarak düzenlenmesine karşın, BM meseleyi tamamen insan haklarının korunması çerçevesinde ele

aldı. Bu yaklaşımın gerisinde azınlıkların en iyi biçimde genel olarak insan haklarına saygının

geliştirilmesiyle korunacağı düşüncesi yatıyordu. Bunun en somut göstergesi, BM Antlaşmasında azınlıkların korunmasıyla ilgili herhangi bir düzenlemeye yer verilmemesi, hatta azınlık sözcüğünün dahi kullanılmamasıydı. BM döneminde eşitliğin sağlanmasını ve ayrımcılığın

önlenmesini hedef alan genel insan hakları rejiminin benimsenmesiyle azınlıklara yalnızca

ayrımcılığı önleyici negatif haklar verilirken, azınlıkların özelliklerini koruyup sürdürmelerini

sağlayacak pozitif haklar tanınmadı. İkinci Dünya Savaşı sonrasında yapılan barış antlaşmaları

da azınlıklar konusunda BM Antlaşmasına benzer bir biçimde kaleme alındılar. Eşitlik ve ayrım

gözetmeme ilkeleri temelinde insan haklarına saygının sağlanmasıyla azınlıkların haklarının

korunacağı anlayışı 9 Aralık 1948’de kabul edilen “Soykırım (Jenosit) Suçunun Önlenmesi ve

Cezalandırılması Sözleşmesi”18 ile 10 Aralık 1948 tarihli “İnsan Hakları Evrensel Bildirgesi” tarafından da benimsendi.

B) BM Örgütünün Azınlıklar Konusundaki Bakışının Değişmesi ve Kişisel ve Siyasal

Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin 27. Maddesi

Zaman içerisinde azınlıkların haklarının yalnızca eşitlik ve ayrım gözetmeme ilkeleri

üzerinde temellenen insan hakları çerçevesinde korunamayacağı, insan haklarının yanı sıra

azınlık haklarına da yer verilmesi gerektiği düşüncesi BM bünyesinde ağırlık kazanmaya başladı. Bunun sonucu olarak azınlıkların korunması amacıyla 1947’de “Ayrımcılığın Önlenmesi

ve Azınlıkların Korunması Alt Komisyonu” oluşturuldu. Ayrıca İkinci Dünya Savaşının ardından belirli azınlık gruplarının haklarını düzenleyen ikili antlaşmalar yapıldı, çeşitli bildiriler

yayınlandı. BM Genel Kurulu da 10 Aralık 1948’de aldığı kararla azınlıkların kaderine kayıtsız

kalamayacağını vurguladı. Ayrıca Genel Kurul, BM Antlaşmasının 13. maddesinde kendisine

verilen yetkiye dayanarak gündeme gelen somut olaylar çerçevesinde azınlık sorunlarıyla ilgilenmeye başladı.

Genel Kurul’un bu girişimlerini BM uzmanlık kuruluşlarının azınlıkların pozitif haklarının korunmasına yönelik çalışmaları izledi. Bunlar, 1966 yılında kabul edilip 1976’da yürürlü18. Sözleşme’de azınlıkların yalnızca fizik olarak var olma hakları tanınırken, kimlik haklarına yer verilmedi ve

azınlık kimliğinin sürdürülmesi sorunu yalnızca insan hakları çerçevesinde düzenlendi. Bu konuda bkz. Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 129; Alpkaya, Gökçen “Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukuku Bağlamında Azınlıklara İlişkin

Bazı Veriler”, İnsan Hakları Yıllığı, C. XIV, (1992), s. 149-150.

13

14

ğe giren “Ekonomik, Sosyal ve Kültürel Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesi” ile “Kişisel ve Siyasal

Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesi” ve “Sözleşmeye Ek Seçmeli Protokol” ile önemli bir aşamaya

ulaştı. Burada uluslararası insan hakları hukukunda evrensel nitelikte olan ve hukuki bağlayıcılığa sahip bulunan azınlık haklarına ilişkin ilk düzenleme niteliğindeki Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar

Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin 27. maddesi özellikle dikkat çekiyordu.

27. madde, belirli bir ülkede bulunan belli bir azınlığa mensup kişilerin değil de,

Sözleşme’ye taraf bütün devletlerdeki etnik, dinsel ve dilsel azınlıklara mensup kişilerin haklarını tanıyıp güvence altına almaya ve uluslararası hukukta azınlıkların kimlik haklarını sağlamaya yönelik ilk ciddi girişim niteliğindedir. Böylesine önemli bir nitelik taşıyan 27. madde şu

hükmü içermektedir:

“Etnik, dinsel ya da dilsel azınlıkların bulunduğu ülkelerde, bu azınlıklara mensup kişiler, gruplarının diğer üyeleriyle birlikte, kendi kültürlerini yaşamak, kendi dinlerini açıkça ilan etmek ve

uygulamak, ya da kendi dillerini kullanmak hakkından yoksun bırakılamazlar.” 19

Maddenin düzenlenmesiyle taraf devletler, her koşulda, “gruplarının diğer üyeleriyle

birlikte azınlıklara mensup kişilerin topluluk olarak” kendi dillerini kullanma, kendi dinlerini

açıklama ve uygulama ile kendi kültürlerinden yararlanma haklarını tanıma yükümlülüğü altına sokulmuşlardır. Burada “gruplarının diğer üyeleriyle birlikte azınlıklara mensup kişilerin

topluluk olarak” ifadesinin kullanılması azınlıklara mensup kişilerin anadillerini kullanmalarının ve dinsel ibadetleri ile çeşitli kültürel faaliyetlerini yerine getirmelerinin yalnızca özel

hayatları bakımından geçerli olmadığını ortaya koymaktadır. Buna göre azınlıklara mensup

kişiler bu haklarını topluluk olarak diğer grup üyeleriyle beraber hayatın diğer alanlarında da

kullanabileceklerdir.

27. madde sözleşmeci devletlere iki ayrı sorumluluk yüklemektedir: 1) Azınlıkların kendi kültürlerini, dinlerini ve dillerini koruma ve geliştirme yönündeki faaliyetlerine karışmama

gibi negatif bir tutum takınacaklardır; 2) Azınlıkların bu yöndeki faaliyetlerini kolaylaştırıcı uygun önlemler alma, böylece azınlık ile çoğunluk arasında gerçek eşitliği sağlama gibi pozitif bir

yükümlülük üstleneceklerdir.20 27. maddeyle ilgili olarak belirtilmesi gereken bir diğer husus

ise, bu maddenin korumasından yalnızca vatandaşların değil, vatandaş olmayanların da yararlanabilmeleridir. BM İnsan Hakları Komitesi 1986’da Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesi ile ilgili olarak yaptığı Genel Yorum’da, Sözleşme’de tanınan haklardan herkesin, hatta

uyruksuzların dahi yararlanabileceklerini belirtmiştir. Komite, ayrıca, 27. madde uyarınca azınlık oluşturan yabancıların, gruplarının diğer üyeleriyle birlikte, kendi kültürlerinden yararlanma, dinî inançlarının gereklerini yerine getirme ve kendi dillerini kullanma hakkından yoksun

bırakılamayacaklarını vurgulamıştır.21 Böylece 27. madde yalnızca vatandaşların azınlık sayılma19. Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesi için bkz. Brownlie, Ian (ed.), Basic Documents in International

Law, 2nd ed., Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1972, s. 162-181.

20. Thornberry, Patrick, International Law and the Rights of Minorities, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1994, s. 185186. Ayrımcılığın Önlenmesi ve Azınlıkların Korunması Alt Komisyonu Özel Raportörü Capotorti de 27. maddede

düzenlenen haklara işlerlik kazandırmak amacıyla taraf devletlerin bu konuda etkin önlemler almaları gerektiğini,

devletlerin yalnızca pasif bir tutum takınmaları durumunda bu hakların etkisizleşeceklerini belirtmiştir. Capotorti,

op.cit., para. 588.

21. Bkz. Pejic, op.cit., s. 672’den “General Comment No. 15”, adopted 22 July 1986, 27 UN GAOR, Human Rights

Committee, 696th Meeting, UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1, 1989. BM İnsan Hakları Komitesinin 27. maddeye ilişkin olarak 1994’te yaptığı diğer bir Genel Yorum’da da bu maddenin korumasından yararlanmanın vatandaşlık

şartına bağlı olmadığı açıkça belirtilmiştir. Bu görüşe dayanak olarak Komite, Sözleşme’nin 2/1. maddesinde her

taraf devletin kendi ülkesinde bulunan ve kendi yetkisine tabi herkese bu Sözleşme ile tanınan hakları sağlamayı

taahhüt ettiğini, bunun tek istisnasını 25. madde ile siyasi haklardan yararlanmanın ve kamu hizmetine girme

hakkının yalnızca vatandaşlara tanınmış olmasının oluşturduğunu vurgulamıştır. Üstelik, bu Genel Yorum’da İnsan

Hakları Komitesi, 27. madde hükümlerinden yararlanabilmek için azınlığa mensup kişilerin bulundukları ülkelerde

sından, vatandaş olmayanların da korunmasına doğru eğilimi başlatan düzenleme olmuştur.

Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesiyle ilgili olarak belirtilmesi gereken bir

diğer önemli husus, getirdiği uluslararası uygulama önlemleri ve oluşturduğu koruma mekanizması ile azınlık haklarının korunması açısından en ileri sözleşme olmasıdır.

Son olarak, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti’nin (KKTC) yasama organı olan Cumhuriyet

Meclisinin 19 Temmuz 2004 tarihli birleşiminde oy birliğiyle Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesini iç hukukun bir parçası olarak kabul ettiğini belirtmek gerekmektedir. Bundan

ötürü Sözleşme, dolayısıyla da 27. madde KKTC bakımından hukuken bağlayıcıdır.

C) Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Yönünde Kabul Edilen Belgeler

BM bünyesinde azınlıkların korunmasıyla ilgili olarak sürdürülen bir diğer çalışma, ırk

ayrımcılığının kaldırılması yönündeki faaliyetler olmuştur. Konu, 1950’li yılların sonlarında birçok ülkede etnik, dinsel ve ulusal ayrımcılık hareketlerinin yaygınlık kazanması üzerine BM’nin

gündemine gelmiştir. Konuyla ilgili ilk önemli adım BM Eğitim, Bilim ve Kültür Örgütü (UNESCO) tarafından atılmıştır. UNESCO Genel Konferansı tarafından 14 Aralık 1960’da benimsenen

ve 22 Mayıs 1962’de yürürlüğe giren “Eğitimde Ayrımcılığa Karşı Sözleşme” eğitimde her türlü

ayrımcılığı yasaklamış, taraf devletlere eğitimde ayrımcılık içeren her türlü yasa hükümleri ile

yönetsel yönergeleri kaldırma ve yönetsel uygulamalara son verme yükümlülüğü getirmiştir.

Azınlık oluşturan gruplara hem kişi, hem de kişilerden oluşan grup olarak belli haklar tanıyan

Sözleşme, ilgili grup lehine özel koruyucu önlemlerin meşruiyetini tanımıştır.

İkinci ciddi adım, “Her Türlü Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Birleşmiş Milletler

Bildirgesi”nin 20 Kasım 1963’te BM Genel Kurulunda kabul edilmesiyle atılmıştır. Bildirge ile

tüm devletler ırk ayrımcılığı yaratan ve bunu sürdüren iç hukuk düzenlemelerini yürürlükten

kaldırmaya, ırk ayrımcılığını engelleyen yasaları benimsemeye ve ırk ayrımcılığına yol açan

önyargılarla mücadele etmek üzere önlemler almaya davet edilmişlerdir.

Üçüncü gelişmeyi “Her Türlü Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Uluslararası Sözleşmesi”nin

4 Ocak 1969’da yürürlüğe girmesi oluşturmuştur. Sözleşme, ırk, renk, ulusal ya da etnik soy ya

da köken temelinde ayrımcılığı yasaklamakta, etnik gruplar bakımından eşit koşulların yaratılması gerektiğini belirtmektedir. Sözleşme’nin temel amacı, farklı ulusal grupların pozisyonları

arasında denge kurmak, özellikle de mağdur durumda olan azınlıklara destek vermektir.22

Her Türlü Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Uluslararası Sözleşmesi de KKTC Cumhuriyet

Meclisinin 19 Temmuz 2004 tarihli birleşiminde oy birliğiyle iç hukukun parçası olarak kabul

edildiğinden, Sözleşme, KKTC’yi hukuken bağlamaktadır.

sürekli ikamet etmek zorunda olmadıklarını, göçmen işçilerin veya ülkede bulunan diğer grupların azınlık grubu

oluşturmaları halinde 27. maddeden yararlanabileceklerini belirtmiştir (UN Human Rights Committee, “General

Comment No. 23 (50) on Article 27/Minority Rights”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. XV, (1994), s. 235, para. 5.15.2). Zaten, 27. madde taslağının Genel Kurul’un Üçüncü Komitesi tarafından görüşüldüğü sırada taslakta yer alan

“herkes” ifadesinin “vatandaşlar” ifadesiyle değiştirilmesi yönünde Hindistan temsilcisinin sunduğu önerinin reddedilmesi ile bu yöndeki anlayış o zamandan ortaya konulmuştur. Bkz. Nowak, Manfred “The Evolution of Minority

Rights in International Law”, Brölmann, Catherine, René Lefeber and Marjoleine Zieck (eds.), Peoples and Minorities in International Law, Dodrecht, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1993, s. 116’dan UN Doc. A / C. 3 / SR. 1103, 1961.

22. Arsava, Ayşe Füsun “Azınlık Hakları ve Bu Çerçevede Ortaya Çıkan Düzenlemeler”, Prof. Dr. Gündüz Ökçün’e

Armağan, Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi, C. XLVII, No. 1-2, (Ocak-Haziran 1992), s. 56.

15

16

D) Ulusal ya da Etnik, Dinsel ve Dilsel Azınlıklara Mensup Kişilerin Haklarına İlişkin

Bildirge

BM bünyesinde azınlıklar konusunun ağırlıklı olarak insan haklarının korunması çerçevesinde ele alınması 1990’lı yıllara kadar devam etmiştir. Bu dönemde Sovyet Blokunun

yıkılmasıyla Doğu Avrupa’da ve Balkanlar’da yaşanan etnik çatışmaların ve azınlık sorunlarının

etkisiyle azınlıkların doğrudan azınlık haklarına ilişkin metinler çerçevesinde korunması gerektiği görüşü ağırlık kazanmıştır.23 Bu anlayış değişikliğinin ilk somut sonucu, 27. maddeden esinlenilerek hazırlanan “Ulusal ya da Etnik, Dinsel ve Dilsel Azınlıklara Mensup Kişilerin Haklarına

İlişkin Bildirge”nin 18 Aralık 1992’de BM Genel Kurulu tarafından kabul edilmesi olmuştur.

Bildirge’nin önemi, hukuki bağlayıcılığa sahip olmasa da yalnızca azınlık haklarını konu alan

ilk uluslararası belge olması24 ve BM uygulamasında ayrımcılığın önlenmesinden azınlıkların

korunmasına bir geçiş niteliğine sahip bulunmasıdır.25

Bildirge’nin getirdiği düzenlemelere bakıldığında, özetle, BM’ye üye devletlere hem

mevzuatta, hem de uygulamada azınlıkların kimliklerini tanıma, bunların geliştirilmesine ilişkin önlemler alma ve asimilasyonu yasaklama yükümlülüğünün getirildiği görülmektedir.

Hukuken bağlayıcı bir belge olmaması Bildirge’nin azınlıkların korunması konusundaki

etkisini sınırlamakla birlikte, BM’nin düzenlediği Dünya İnsan Hakları Konferansı sonunda 25

Haziran 1993’te kabul edilen Viyana Bildirisi ve Eylem Programında azınlık haklarının evrensel

olarak korunmasında Bildirge ölçüt olarak alınmıştır.26 Böylece Bildirge önemli bir referans

kaynağı olmuştur.

23. Bu konuda bkz. Lerner, Natan “The Evolution of Minority Rights in International Law”, Catherine Brölmann,

René Lefeber and Marjoleine Zieck (eds.), Peoples and Minorities in International Law, Dodrecht, Martinus Nijhoff

Publishers, 1993, s. 91-100.

24. Alfredsson, Gudmundur and Alfred de Zayas, “Minority Rights: Protection by the United Nations”, Human

Rights Law Journal, C. XIV, No. 1-2 (1993), s. 3.

25. Oran, Küreselleşme ve Azınlıklar, s. 132.

26. Bu konuda bkz. Özdek, E. Yasemin, “1990’larda İnsan Hakları: Sorunlar ve Yönelimler”, İnsan Hakları Yıllığı, C.

XV, (1993), s. 36-37.

II) Bölgesel Örgütlenmeler

A) Avrupa Konseyi ve Azınlıkların Korunması

1) Avrupa İnsan Hakları Sözleşmesi

İkinci Dünya Savaşının ertesinde, başka amaçların yanı sıra, insan haklarının ve temel

özgürlüklerin evrensel düzeyde gerçekleştirilmesi ve korunması amacıyla kurulan BM’nin ardından bölgesel örgütlenmelere ağırlık verilerek daha etkin koruma mekanizmaları oluşturulmaya çalışılmıştır. Bu bağlamda 1949’da Avrupa Konseyi (AK) kurulmuştur.

AK’nin kurulmasından sonra insan haklarının ve temel özgürlüklerin korunması ve geliştirilmesi için hukuki bağlayıcılığı olan bir belgenin hazırlanması çabası içerisine girilmiştir.

Bunun sonucunda 3 Eylül 1953’te yürürlüğe giren “İnsan Haklarını ve Temel Özgürlüklerini

Korumaya Dair Sözleşme”- kısaca “Avrupa İnsan Hakları Sözleşmesi” (AİHS) hazırlanmıştır.

İnsan hakları alanında bugüne kadarki en etkili denetim mekanizmasını oluşturmasına rağmen AİHS ve Sözleşme’ye ek protokollerde yer alan haklar çok büyük çoğunlukla kişisel

ve siyasal haklardan oluşmuş, azınlık haklarıyla ilgili herhangi bir düzenlemeye yer verilmemiştir.27 Yalnızca Sözleşme’nin 14. ve AİHS’ye Ek 12 Numaralı Protokol’ün 1. maddelerinde

ayrımcılığın önlenmesi ve eşitliğin sağlanması temelinde düzenlemelere gidilmiştir. “Ayrımcılık Yasağı” başlığını taşıyan 14. maddede Sözleşme’de düzenlenen hak ve özgürlüklerden

yararlanmanın cinsiyet, ırk, renk, dil, din, siyasal ya da başka bir görüş, ulusal ya da toplumsal

köken, bir ulusal azınlıktan olma, mülkiyet, doğum ve benzeri başka bir statü ayrımı gözetilmeksizin herkes bakımından geçerli olacağı vurgulanmıştır. “Genel Olarak Ayrımcılığın Yasaklanması” başlığını taşıyan Ek 12. Protokol’ün 1. maddesi ise şu düzenlemeyi içermektedir:

“1. Hukuken temin edilmiş olan tüm haklardan yararlanma, cinsiyet, ırk, renk, dil, din, siyasi

veya diğer kanaatler, ulusal veya sosyal köken, ulusal bir azınlığa mensup olma, servet, doğum

veya herhangi bir diğer statü bakımından hiçbir ayrımcılık yapılmadan sağlanır.

2. Hiç kimse, 1. fıkrada belirtildiği şekilde, hiçbir gerekçeyle, hiçbir kamu makamı tarafından

ayrımcılığa maruz bırakılamaz.”28

Böylece, azınlıklara mensup kişiler, azınlık koruma hükümleri düzenlenmemiş olmasına karşın, ayrımcılığın önlenmesi ve eşitliğin sağlanması temelinde düzenlenen kişisel ve

siyasal hak ve özgürlüklerle ilgili hükümlerden yararlanabilmektedirler.

Azınlıklara pozitif haklar tanımamakla birlikte Sözleşme, hak ve özgürlükler alanında

bugüne kadar uluslararası düzeyde gerçekleştirilmiş en etkili denetim mekanizmasını oluşturması bakımından çok önemli bir yere sahiptir. Avrupa İnsan Hakları Mahkemesi (AİHM) ile

AK Bakanlar Komitesinden oluşan söz konusu denetim mekanizmasının sağladığı korumadan

azınlıklara mensup kişiler de yararlanabilmektedirler. Buna göre, herhangi bir azınlığa mensup olan kişiler bundan dolayı ayrımcılığa uğradıkları gerekçesiyle AİHM’ye bireysel başvuruda

bulunabilirler. Fakat bu kişiler bir azınlık grubu yerine kişiler topluluğu olarak işlem görürler.

Azınlığa mensup kişilerin bireysel başvuru hakkını kullanabilmeleri için bizzat ayrımcılık uygu27. Sözleşme’de azınlıklarla ilgili herhangi bir düzenlemeye gidilmemesinin temel nedenini ulusal birliklerinin

korunması yönünde taraf devletlerin duydukları hassasiyet oluşturuyordu.

28. http://www.humanrights.coe.int/Prot12/Protocol%2012%20and%20Exp%20Rep.htm, 31.08.2011.

17

18

lamasının mağduru olmaları gerekir. Bir azınlık üyesi diğer azınlık mensupları adına başvuruda

bulunamaz.

Sözleşme’de düzenlenen haklarının ihlâl edildiği gerekçesiyle azınlıkların grup olarak

AİHM’ye başvurmaları mümkün olmamakla birlikte, Belçika’da 1968’de patlak veren dil çatışmaları, İsveç’te 1973’te ortaya çıkan okullardaki din eğitimi sorunu ve İngiltere’de 1973’te

doruğa ulaşan Müslüman azınlığın sorunları başta olmak üzere azınlıkların sorunlarıyla ilgili

çeşitli başvurular Avrupa İnsan Hakları Komisyonu (AİHK) ve AİHM’de ele alınmıştır.29 Komisyon ve Mahkeme’de bu başvurular azınlık hakları çerçevesinde değil de bireysel haklar ekseninde ele alınmakla birlikte, çeşitli tarihlerde yapılan başvurularla ilgili olarak bu organlarda

azınlık hakları çerçevesinde kararlar da verilmiştir.30

Son olarak, AİHS hükümlerinin Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta geçerli olduğunu belirtmek gerekmektedir. Bununla birlikte, gerek Loizidou v. Türkiye (No. 15318/89), gerekse Kıbrıs v. Türkiye davalarıyla (No. 25781/94) ilgili kararlarında AİHM, KKTC’yi “Türkiye’ye bağlı yerel yönetim (subordinate local administration)” olarak değerlendirdiğinden dolayı, Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta meydana

gelebilecek her türlü hak ihlâlinden Türkiye sorumlu tutulmaktadır. 31 Ağustos 2011 itibariyle

Ek 12. Protokol Türkiye tarafından onaylanmadığından ötürü Protokol’ün bağlayıcılığı yoktur.

Dolayısıyla Protokol, Kuzey Kıbrıs bakımından geçerli değildir.

2) Bölgesel Diller ya da Azınlık Dilleri Avrupa Şartı

AİHS’de ayrımcılığın önlenmesi ve eşitliğin sağlanması dışında azınlık haklarıyla ilgili

herhangi bir düzenlemeye yer verilmemekle birlikte, zaman içerisinde AK bünyesinde bu konuda var olan eksikliği gidermeye yönelik çalışmalar yapılmaya başlanmıştır. Bunlar, 1989’dan

sonra Doğu Blokunda görülen köklü değişikliklerle birlikte etnik çatışmaların ve azınlık sorunlarının dünya gündeminin ilk sıralarına yerleşmesiyle yoğunluk kazanmıştır. Sonuçta, azınlık hakları konusunda AK bünyesinde sürdürülen faaliyetler 1992’de “Bölgesel Diller ya da

Azınlık Dilleri Avrupa Şartı”nın, 1995’te de “Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve

Sözleşme”nin kabul edilmesiyle somut sonuçlarını vermiştir.

1 Mart 1998’de yürürlüğe giren Bölgesel Diller ya da Azınlık Dilleri Avrupa Şartının 1.

maddesinde, bir devlette çoğunluktan daha az nüfusa sahip bir vatandaş grubu tarafından

geleneksel olarak konuşulan, söz konusu devletin resmî dil veya dillerinden farklı olan ve devletin resmî dil veya dillerinin diyalektlerini ve göçmenlerin dillerini içermeyen dillerin bölgesel

diller veya azınlık dilleri sayıldıkları ve Şart’ın konusunu oluşturdukları belirtilmektedir. Görüldüğü gibi, Şart’ta düzenlenen haklardan yararlanabilmek için, açık bir şekilde, vatandaş olma

koşulu aranmaktadır.

29. Bu konuda bkz. Ataöv, Türkkaya, “Azınlıklar Üstüne Bazı Düşünceler”, Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi, C. XLII, No. 1-4, (Ocak-Aralık 1987), s. 50; Hillgruber, Christian and Matthias Jestaedt, The European

Convention on Human Rights and the Protection of National Minorities, çev., Steven Less and Neil Solomon, Koln,

Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1994, s. 23-32.

30. Örneğin, 1981’de Norveç’e karşı yapılan bir bireysel başvuruyla ilgili olarak Komisyon verdiği ön kararında,

özel hayata, aile hayatına, konuta ve haberleşme hakkına saygı gösterilmesini düzenleyen AİHS’nin 8. maddesi uyarınca bir azınlık grubunun kendisine özgü yaşam biçimine saygı gösterilmesi hakkını talep etme hukuki imkânına

sahip olduğunu belirtmiştir. Bundan dolayı AİHK, 8. maddede düzenlenen hakların azınlıkların kendilerine özgü yaşam biçimlerinin korunmasını gerektirdiğini vurgulamıştır. Çavuşoğlu, Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukukunda Azınlık

Hakları, p. 98’den Komisyon’un G ve E / Norveç, 3.10.1983, (No. 9278/81-9415/81) başvurusuyla ilgili kararı.

Komisyon’un yanı sıra AİHM de konuyla ilgili çeşitli kararlar vermiştir. Örneğin, ileride geniş şekilde ele alacağımız

Kıbrıs v. Türkiye davasında (No. 25781/94) (4. Devlet başvurusu) AİHM 10 Mayıs 2011 tarihli kararında Kıbrıs’ın

Karpaz bölgesinde yaşayan Rumlarla ilgili olarak AİHS’nin çeşitli hükümlerinin Türkiye tarafından ihlâl edildiği saptamasında bulunmuştur.

Şart’ın ilke ve amaçlarının belirtildiği 2. bölümdeki 7. maddede taraf devletlerin özel

hayatta ve kamu hayatında bölgesel dillerin veya azınlık dillerinin konuşulması ve yazı dilinde

kullanılması yönünde herhangi bir engel çıkartmayacakları belirtilmiştir. Bunun da ötesinde

sözleşmeci devletlerin bu konuda var olan engelleri ortadan kaldıracakları, hatta bu dillerin

kullanımını teşvik edecekleri, bunların öğretilmesi konusunda her türlü önlemi alacakları ve

bu konuda diğer taraf devletlerle gerekli işbirliği içerisine girecekleri vurgulanmaktadır. Şart’ın

3. bölümünde ise, bölgesel dillerin veya azınlık dillerinin eğitim ve kültür alanında, mahkemelerde, yönetim organları önünde ve kamu hizmetlerinde, kitle iletişim araçları ile ekonomik

ve sosyal hayatta kullanımını sağlamak ve yaygınlaştırmak konusunda taraf devletlerin uzun

vadede almaları gereken önlemler düzenlenmektedir.

3) Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve Sözleşme ve Uygulanması

AK bünyesinde kabul edilen bir diğer önemli sözleşme, 1 Şubat 1998’de yürürlüğe

giren “Ulusal Azınlıkların Korunmasına İlişkin Çerçeve Sözleşme”dir. Çerçeve Sözleşme ulusal

azınlıkların korunması konusunda hukuki bağlayıcılığa sahip çok taraflı ilk belge niteliğindedir.

Sözleşme, bir çerçeve sözleşme niteliğinde olduğundan dolayı, doğrudan uygulanabilir

hükümler yerine çoğunlukla taraf devletlerin kendi iç hukuklarında yapmaları gereken yasal düzenlemeleri ve almaları gereken önlemleri belirleyen düzenleyici nitelikte hükümler içermektedir. Ulusal azınlıklar meselesinin her taraf devletteki özel koşulların dikkate alınmasını gerektiren

bir konu olduğu görüşünden hareketle Sözleşme’de taraflara geniş bir takdir yetkisi tanınmıştır.31

AİHS’de düzenlenen haklara azınlık hakları hukukunun gerekleri ile bağdaşan ekler

getiren Çerçeve Sözleşme’nin32 2. bölümünde Sözleşme’ye taraf devletlerin ulusal azınlıklara

mensup kişilerin kendi dillerinde görüş edinme, haber ve fikir alma ve verme özgürlüklerini

tanıyacakları, kendi iletişim araçlarını kurma ve kullanma imkânını sağlayacakları ifade edilmektedir. Bunların dışında sözleşmeci devletlerin, bu kişilerin geleneksel olarak ya da önemli

sayıda yaşadıkları bölgelerde, talep etmeleri ve böyle bir talebin gerçek bir ihtiyaca karşılık

ilişkin olması halinde, azınlığa mensup kişilerle idarî makamlar arasındaki ilişkilerde azınlık dillerinin kullanılmasına imkân verecek koşulları sağlamaya gayret edecekleri belirtilmektedir.

Bu bölümde dikkat çekici bir diğer husus, taraf devletlerin ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin

azınlık dillerinde isim ve soy isim kullanma hakkına sahip olduklarını ve tabelalarda, yazılarda

ve kamuya açık özel nitelikli diğer açıklamalarda azınlık dillerini kullanabileceklerini kabul etmeleridir. Bunun da ötesinde sözleşmeci devletler azınlıkların geleneksel olarak önemli oranda

yaşadıkları bölgelerde, yeterli talep olması durumunda, geleneksel yerel adlar, sokak adları ve

kamuya yönelik diğer topografik işaretlerde azınlık dillerinin de kullanılması yönünde gayret

gösterme taahhüdünde bulunmuşlardır. Ayrıca, taraf devletlerin ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin kendi özel eğitim ve öğretim kurumlarını kurma ve yönetme ile kendi azınlık dillerini öğrenme haklarını tanıyacaklarına ve bu yönde gerekli olanakları yaratacaklarına değinilmektedir.

Gevşek bir denetim sistemi getiren Çerçeve Sözleşme’de dikkat çekici bir diğer düzenleme 30. maddede yer almaktadır. Bu düzenlemeyle sözleşmeci devletlere Sözleşme’nin ülkenin hangi bölgeleri bakımından geçerli olacağını bir bildirim ile belirleme hakkı tanınmıştır. Bu

bildirim geri alınabilecek nitelikte olmasına rağmen, geri alma AK Genel Sekreterinin konuyla

ilgili duyuruyu aldığı tarihten itibaren üç aylık bir sürenin geçmesinin ardından geçerlilik kazanmaktadır.

31. Çavuşoğlu, Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukukunda Azınlık Hakları, s. 17. Bu konuda ayrıca bkz. Gilbert, Geoff,

“The Council of Europe and Minority Rights”, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, (February 1996), s. 174

ve 188.

32. Çavuşoğlu, Uluslararası İnsan Hakları Hukukunda Azınlık Hakları, s. 68.

19

20

B) Avrupa Birliği ve Azınlıkların Korunması

Avrupa Birliği (AB), BM ve AK’den farklı olarak ekonomik amaçlardan yola çıkılarak

oluşturulan ve ekonomik bütünleşmenin hedef alındığı bir örgüt olduğu için, AB’de insan hak

ve özgürlükleri ile azınlık haklarına yönelik çalışmaların BM ve AK bünyesinde sürdürülenlere

oranla cılız kaldığı görülmektedir. Ancak, Avrupa Toplulukları Adalet Divanının (ATAD) kararları

sayesinde ve 1 Temmuz 1987’de yürürlüğe giren Tek Senet’le hız kazanan siyasi bütünleşmeye

yönelik çabaların bir uzantısı olarak hak ve özgürlükler alanında önemli gelişmeler kaydedilmiştir. Ayrıca Avrupa Parlamentosunun (AP), AB Konsey ve Komisyonunun konuyla ilgili çabaları söz konusudur. Bu organların kabul ettikleri çeşitli belgelerde genel olarak insan hakları,

ayrımcılığın önlenmesi, ırkçılıkla mücadele, çoğulcu demokrasi, hukukun üstünlüğü ve sosyal

adalet konularının önemi vurgulanmış, bunlara saygının Birliğe üyeliğin vazgeçilmez unsuru

olduğu belirtilmiştir.

AB organlarının kararları dışında, Avrupa Topluluklarını kuran antlaşmaların ve onların eklerinin bazılarında da konuyla ilgili doğrudan düzenlemelere yer verilmiştir. Örneğin, 7

Şubat 1992’de Maastricht’te imzalanan Avrupa Birliği Antlaşmasında temel insan haklarına

saygının Birliğe üyeliğin önkoşulunu oluşturduğu ifade edilmiştir. 17 Haziran 1997’de kabul

edilen ve Avrupa Birliği Antlaşmasına değişiklik getiren Amsterdam Antlaşmasında ise ayrımcılığın giderilmesine ilişkin düzenlemelere yer vermiştir.

Ayrımcılığın önlenmesine ilişkin olarak AB bünyesinde kabul edilen iki ayrı belgeye de

değinmek gerekmektedir. Bunlardan birincisi, ırk veya etnik kökene bakılmaksızın kişiler arasında eşit muamele ilkesinin uygulanmasına dair 29 Haziran 2000 tarihli ve 2000/43/EC sayılı

AB Direktifidir. İkincisi ise, AB Temel Haklar Şartıdır. Şart’ın 21/1. maddesi her türlü ayrımcılığı

açık bir şekilde yasaklamaktadır.

Ayrımcılığın önlenmesine yönelik düzenlemeler dışında, AB organları bünyesinde

doğrudan azınlık haklarının korunmasına yönelik çalışmalar da başlatılmış, özellikle AP’de dilsel azınlıklarla ilgili çeşitli kararlar alınmıştır.33

1993’te AB üyesi ülkelerin devlet veya hükümet başkanlarının bir araya geldikleri

Kopenhag Zirvesi konu açısından önemli bir yere sahiptir. Zirve’de, 1989’daki gelişmelerden

sonra bağımsızlıklarını yeni kazanan eski Doğu Bloku üyesi devletlerin tekrar Rusya’nın etkisi

altına girebilecekleri endişesiyle bunların Birliğe nasıl dahil edilebilecekleri ve Birliğin hangi kriterlere göre genişleyeceği konusu tartışılmış, çeşitli kararlar alınmıştır. “Kopenhag Kriterleri” olarak tanımlanan kararlar bütününün ilk bölümünü oluşturan bu kararlarla,34 başta

Orta ve Doğu Avrupa ülkeleri olmak üzere, AB’ye üye olmak isteyen aday ülkelerin, AB müktesebatına uyumu gerçekleştirmenin yanı sıra, uymaları gereken siyasal ve ekonomik ölçüt33. AP’nin konuyla ilgili çeşitli kararları için bkz. Nas, Çiğdem, “Avrupa Parlamentosu’nun Etnik Azınlıklara Bakışı

ve Türkiye”, Faruk Sönmezoğlu (der.), Uluslararası Politikada Yeni Alanlar, Yeni Bakışlar, İstanbul, Der Yayınları,

1998, s. 392-393.

34. “Kopenhag Kriterleri” olarak adlandırılan ve bir ülkenin AB üyesi olabilmesi için sahip olması gereken temel

nitelikleri saptayan kriterler yalnızca 1993 Kopenhag Zirvesinde alınan kararlardan oluşmamaktadır. Kopenhag

Kriterleri, Kopenhag Zirvesinin yanı sıra, 1995 Madrid ve 1997 Lüksemburg Zirvelerinde alınan kararların bütününü simgelemektedir. Buna göre, Madrid Zirvesinde AB politikalarının uyumlu olarak yürütülmesini sağlayabilmek

amacıyla, katılım ertesinde aday ülkelerin idarî yapılarının uyumlaştırılmasının gerekli olduğuna dikkat çekilmiştir.

Lüksemburg Zirvesinde ise, AB müktesebatının ulusal mevzuata geçirilmesinin yeterli olmadığı, müktesebatın etkili

bir biçimde uygulanmasının asıl önemli konuyu oluşturduğu vurgulanmıştır. Böylece, ilk kez Kopenhag Zirvesinde

ortaya konulan Kopenhag Kriterleri, Madrid ve Lüksemburg Zirvelerinde alınan kararlarla geliştirilmiştir. Baykal,

Sanem “Kopenhag Kriterleri”, Baskın Oran (ed.), Türk Dış Politikası, Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olaylar, Belgeler,

Yorumlar, C. II, İstanbul, İletişim Yayınları, 2001, s. 332.

ler belirlenmiştir. Burada demokrasi, hukukun üstünlüğü, insan ve azınlık haklarına saygı ve

bunların korunması konuları siyasi ölçütler olarak ortaya konulurken, insan ve azınlık hakları

konularında Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Teşkilatı (AGİT) ile AK’nin temel belgelerine atıfta bulunulmuştur. Bundan yola çıkılarak, AB’ye üye olmak isteyen devletlerden öncelikle AİHS’ye

taraf olmaları, AİHM’ye bireysel başvuru hakkını tanımaları ve azınlık hakları ile ilgili temel

metinleri onaylamaları istenmiştir. Bu hususlar göz önünde bulundurulduğunda AB ile üyelik

ilişkisi içerisine girmek isteyen devletlerin Avrupa insan ve azınlık hakları rejiminin bir parçası

olmak durumunda oldukları görülmektedir.

Son olarak, azınlıklar konusuyla ilgili düzenlemeler getiren ve AB ile AT Antlaşmalarına

değişiklik getiren Lizbon Antlaşmasına değinmek gerekmektedir. 1 Aralık 2009’da yürürlüğe

giren Lizbon Antlaşması ile AB Antlaşmasına madde 1a’nın eklendiği belirtilmiştir. Madde şu

düzenlemeyi içermektedir:

“Birlik, insan onuruna saygı, özgürlük, demokrasi, eşitlik, hukukun üstünlüğü ve azınlıklara

mensup kişilerin hakları da dahil olmak üzere insan haklarına saygı değerleri üzerinde kurulmuştur. Bu değerler, çoğulculuğun, ayrım gözetmemenin, hoşgörünün, adaletin, dayanışmanın

ve kadın ile erkek arasındaki eşitliğin olduğu bir toplumda üye devletler bakımından ortaktır.”35

Bunun dışında madde 5b’nin Antlaşma metnine eklendiği belirtilmiştir. Düzenleme

şu hükmü içermektedir: “Birlik, politikalarını ve faaliyetlerini tanımlamada ve uygulamada,

cinsiyete, ırksal veya etnik kökene, dine veya inanca, engelli olmaya, yaşa veya cinsel tercihe

dayalı ayrımcılıkla mücadeleyi amaçlar.”36

C) Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Konferansı/Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Teşkilatı Belgelerinde Azınlık Haklarının Korunması

1989’dan sonra eski Doğu Bloku ülkelerinde yaşanan etnik gerilimlerin ve çatışmaların neden

olduğu trajik olaylar uluslararası belgelerde azınlık haklarına ilişkin yeni standartların geliştirilmesinde belirleyici olmuş, bu konuda Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Konferansı (AGİK) Süreci/

AGİT öncü rol oynamıştır.

Her ne kadar AGİT bünyesinde azınlık haklarıyla ilgili çalışmalar esas olarak 1989 sonrası dönemde yoğunluk kazanmışsa da, bu yönde atılan adımlar Ağustos 1975’te toplanan

Helsinki Zirvesi sonunda 1 Ağustos 1975’te kabul edilen Helsinki Sonuç Belgesine/Son Senet’e

kadar dayanmaktadır. İnsan ve azınlık haklarıyla ilgili ayrıntılı düzenlemeler getirmemekle ve

hukuki bağlayıcılığı bulunmamakla birlikte Sonuç Belgesi, azınlıkların uluslararası korunmasında en ileri düzenlemeleri getiren AGİT’in bugünkü biçimini almasında ilk kilometre taşı olması

bakımından büyük öneme sahiptir.37

Helsinki Sonuç Belgesinin imzalanmasıyla Doğu ve Batı Blokları arasında oluşan olumlu hava zamanla yerini olumsuzluğa bırakmıştır. Yapılan toplantılardan beklenen sonuçlar elde

edilememekle birlikte, 1980-1983 Madrid İzleme Toplantısının ardından kabul edilen Madrid

Belgesinde konumuzla ilgili önemli bir düzenlemeye yer verilmiştir. Belge’nin 1. bölümünde

katılan devletler ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin haklarına saygıyı sağlama ile azınlık hakla35. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2007:306:0010:0041:EN:PDF, 31.08.2011.

36. Ibid.

37. Sonuç Belgesinde insan hakları ile ayrımcılığın önlenmesi ve eşitliğin sağlanması temelinde düzenlenen azınlık hakları konuları yalnızca 1. bölümde yer alan “Katılan Devletlerin Karşılıklı İlişkilerine Yol Gösterecek İlkeler

Bildirisi”nin 7. ilkesinde ve 3. bölümde düzenlenmiştir. Helsinki Sonuç Belgesi ve diğer tüm AGİK/AGİT belgeleri

için bkz. http://www.osce.org.

21

22

rından yararlanmaları olanağını yaratmada sürekli bir ilerlemenin önemini vurgulamışlardır.38

1986-1989 Viyana İzleme Toplantısı, azınlık hakları konusunda bir dönüm noktası oluşturmuştur. Toplantı sonunda kabul edilen 19 Ocak 1989 tarihli Viyana Kapanış Belgesinin

18. ilkesinde ayrımcılığın önlenmesine ve eşitliğin sağlanmasına yönelik düzenlemelere yer

verilmesinin yanında, 19. ilkede azınlıklara mensup kişilerin hakları ilk kez doğrudan tanınmıştır. Bu ilkede, katılan devletlerin ülkelerindeki ulusal azınlıkların etnik, kültürel, dilsel ve dinsel

kimliklerinin geliştirilmesi için gerekli şartları koruyacakları ve yaratacakları hükmü düzenlenmiştir.39

AGİK’e taraf devletlerin temsilcilerinin bir araya geldikleri 1990 Kopenhag İnsani Boyut Toplantısı sonunda kabul edilen 29 Temmuz 1990 tarihli Kopenhag Belgesi, bugüne kadar

azınlıklar konusunda en ileri düzenlemeler getiren uluslararası metinlerden birisi, hatta birincisi olmuştur.40 Önceki uluslararası metinlerden farklı olarak Kopenhag Belgesinde azınlık

hakları konusunda var olan standartları aşan düzenlemelere yer verilmesinin nedeni Doğu

Blokunun çözülüşünün ardından patlak veren etnik sorunlara bir çözüm bulma arayışıdır.

4. bölümde yer alan ayrımcılığın önlenmesine ve eşitliğin sağlanmasına yönelik düzenlemelerin yanı sıra, Kopenhag Belgesinde azınlık haklarına ilişkin ayrıntılı ve doğrudan düzenlemelere yer verilmiştir. Belge’nin 32. paragrafında ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin kendi isteklerine karşı herhangi bir asimilasyon girişimine uğramadan etnik, kültürel, dilsel ya da

dinsel kimliklerini tam bir özgürlük içerisinde ifade etmek, korumak ve geliştirmek ile kültürlerini bütün biçimleri altında sürdürmek ve geliştirmek hakkına sahip oldukları ifade edilmiştir.

Kopenhag Belgesinde azınlıkların haklarının gerçekleştirilmesi ve korunması için devletlere getirilen yükümlülükler de sıralanmıştır. Bu çerçevede, öncelikle, katılan devletlerin

topraklarındaki ulusal azınlıkların etnik, kültürel, dilsel ve dinsel kimliklerini koruyacakları,

bu kimliklerinin geliştirilmesine yönelik koşulları yaratacakları ve bu amaçla gereken önlemleri alacakları belirtilmiştir.41 Belge’nin 35. paragrafının 2. maddesinde ise bir başka önemli

düzenlemeye yer verilmiştir. Buna göre, katılan devletlerin azınlıkların etnik, kültürel, dilsel

ve dinsel kimliklerinin korunması konusunda belirlenen amaçları gerçekleştirme yollarından

birisi olarak bu azınlıkların özgül tarihsel ve ülkesel konumlarına denk düşen uygun yerel ya

da özerk yönetimlerin devlet politikalarına uygun olarak yaşama geçirilmesini not ettikleri

vurgulanmıştır.42

1989 sonlarında Doğu Avrupa ülkelerinde reel-sosyalist rejimlerin arka arkaya çökmesi, 1990’da Sovyetler Birliği’ndeki rejimin tıkanma noktasına gelmesi ve iki Almanya’nın

38. İlkeler, para. 15.

39. Viyana Belgesinin 19. ilkesi ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin etnik, kültürel, dilsel ve dinsel kimliklerine kolektif bir koruma ve bunları sürdürme olanağı sağlayan ilk düzenleme olarak değerlendirilmiştir. Nowak, op.cit., s.

107.

40. Bu yönde bkz. Pejic, op.cit., s. 679.

41. Para. 33. Buradaki düzenlemenin azınlıkların grup özelliklerini öne çıkarması bakımından Belge’deki diğer

paragraflardan farklılaştığı belirtilmektedir. Buergenthal, Thomas “The Copenhagen CSCE Meeting: A New Public

Order for Europe”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. XI, (1990), s. 228; Nowak, op.cit., s. 107.

42. 33. paragraf gibi, burada da azınlıklara mensup kişilerin haklarını korumaktan öte grup olarak azınlıkların

korunmasına ilişkin düzenlemeye yer vermiştir. Azınlık hakları bakımından böylesine ileri bir düzenlemenin varlığını, diğer AGİK belgeleri gibi, Kopenhag Belgesinin de hukuki bağlayıcılığa sahip bir belge olmamasında aramak

gerekir. Fakat Macaristan, Kopenhag Belgesindeki söz konusu düzenlemeye uygun olarak 1993’te “Ulusal ve Etnik

Azınlıklar Yasası”nı onaylamıştır. Yasa ile azınlıklar konusunda görev yapacak bir Ombudsman’ın oluşturulmasına

karar verilmesinin yanı sıra, ülkedeki azınlıklara özel yönetim hakkı (self-government right) da tanınmıştır. Bu konuda bkz. Wright, Jane “The OSCE and the Protection of Minority Rights”, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. XVIII, No.

1, (February 1996), s. 197-198.

birleşmesi gibi son derece radikal değişiklikler Kasım 1990’da Paris’te daha önce kararlaştırılmamış bir zirve toplantısının yapılmasına vesile olmuştur. Konferans sonunda imzalanan 21

Kasım 1990 tarihli “Yeni Bir Avrupa İçin Paris Şartı/Yasası” adlı sonuç belgesinde demokrasi,

insan hakları ve hukuk devleti ilkelerinin yeni Avrupa düzenine egemen olacak ilkeler olduğu

belirtilmiş, azınlık haklarıyla ilgili kimi düzenlemeler getirilmiştir.

Paris Zirvesinin ardından Temmuz 1991’de Cenevre’de Ulusal Azınlıklara İlişkin Uzmanlar Toplantısı gerçekleştirilmiştir. İkinci Dünya Savaşı sonrasında Avrupa’da düzenlenen ilk

özel azınlık konferansı olan Cenevre Toplantısı43 sonunda 19 Temmuz 1991’de “Ulusal Azınlıklara ilişkin AGİK Uzmanlar Toplantısı Raporu” açıklanmıştır. Rapor’da, Kopenhag Belgesinde

ortaya konulan kimi ilkeler teyit edilirken, bazı yeni düzenlemelere de yer verilmiştir. Buna

göre, Rapor’un 2. bölümünde ulusal azınlıklar konusunun devletlerin içişleriyle ilgili bir konu

olmaktan çıkıp uluslararası toplumun meşru ilgi alanını oluşturduğu belirtilmiştir.44

Cenevre Raporunun 4. bölümünde, katılan devletlerin, eğer henüz yapmamışlarsa, bir

ulusal azınlığa mensup olma ya da olmama temelinde ayrımcı bir davranışa uğrayan kişiler için

etkin başvuru yolları sağlayacakları belirtilmiştir.45 Bunun yanı sıra Rapor, azınlıkların korunması için uygulanabilecek demokratik yolları saymıştır. Bunlar arasında özellikle eğitim, kültür

ve din konularıyla ilgili olarak azınlıkların temsil edilecekleri danışma ve karar alma organlarının kurulması;46 ulusal azınlıklarla ilgili işlerde seçilmiş organ ve meclislerin oluşturulması;47

özgür ve periyodik seçimler yoluyla belirlenmiş danışma, yasama ve yürütme organlarını içeren yerel ve özerk yönetimlere ve ülkesel temelde özerkliğe yer verilmesi;48 ülkesel temelde

özerkliğin uygulanamadığı durumlarda bir ulusal azınlığın kendi kimliğini ilgilendiren konularda kendi kendini yönetmesinin sağlanması49 ve yerel hükümet biçimlerinin oluşturulması50

hususları yer almaktadır.

Ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişiler bakımından getirdiği bu olumlu düzenlemelere karşın, Rapor’da bütün etnik, kültürel, dilsel ya da dinsel farklılıkların mutlaka ulusal azınlıkların

yaratılmasına yol açmadığı belirtilmiştir.51 Kopenhag Belgesiyle çeliştiği belirtilen bu yaklaşımın azınlıkların varlıklarını tanımada katılan devletlere geniş bir takdir hakkı sağladığı, bundan

dolayı onlar tarafından azınlıkların varlıklarını inkâr etmek için kullanılabileceği ifade edilmiştir.52 Bununla birlikte, Cenevre Toplantısından itibaren bir grubun azınlık olarak nitelendirilebilmesi için etnik, kültürel, dilsel ya da dinsel farklılığın mevcudiyetinin yeterli olmadığı, bu

konuda azınlık bilincinin asıl belirleyici ölçüt olarak kabul edilmeye başlandığı görülmektedir.

Bu tartışmalara karşın, Cenevre Raporu grup haklarının tanınmasına yönelik açılımlar sağlayan hükümler içermesi nedeniyle azınlıkların korunması bakımından AGİK sürecinde önemli

bir aşamayı oluşturmaktadır.

43. Arsava, Ayşe Füsun Azınlık Kavramı ve Azınlık Haklarının Uluslararası Belgeler ve Özellikle Medeni ve Siyasal

Haklar Sözleşmesinin 27. Maddesi Işığında İncelenmesi, Ankara, Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Yayınları, 1993, s. 101.

44. Para. 3.

45. Para. 2.

46. Para. 8.

47. Para. 9.

48. Para. 10.

49. Para. 11.

50. Para. 12.

51. Bölüm II, para. 4.

52. Bu düzenlemeden ötürü AGİK katılımcısı 8 devlet bu yaklaşımın Kopenhag Belgesine uygun olmadığı konusunda çekince koymuşlardır. Cenevre Raporuna yönelik bu eleştiriler için bkz. Roth, Stephen J. “Comments on the

CSCE Meeting of Experts on National Minorities and its Concluding Document”, Human Rights Law Journal, Vol.

XII, (1991), s. 331.

23

24

Cenevre Uzmanlar Toplantısını 1991 Moskova ve 1992 Helsinki belgelerinin kabulü

izlemiştir. Moskova Belgesinde katılan devletler ulusal azınlıklarla ilgili tüm AGİK belgelerini

teyit ederek bu belgelerdeki ilkeleri tam olarak ve gecikmeksizin gerçekleştirecekleri yönünde

taahhütte bulunmuşlardır.53 Helsinki Belgesinde ise katılan devletlere ülkelerinde azınlıkların

bulunduğu bölgelerdeki etnik bileşimi güç kullanarak ya da güç kullanma tehdidiyle değiştirme yasağı getirilmiştir.54

AGİK’in isminin, 1 Ocak 1995’ten itibaren geçerli olmak üzere, “Avrupa Güvenlik ve

İşbirliği Teşkilatı” olarak değiştirileceğinin kararlaştırıldığı Aralık 1994 tarihli Budapeşte Zirvesinden sonra Kasım 1999’da İstanbul Zirvesi toplanmıştır. Zirve’de kabul edilen “Avrupa Güvenlik Şartı”nda ve “İstanbul Zirvesi Deklarasyonu”nda azınlıklarla ilgili düzenlemelere yer verilmiştir. Avrupa Güvenlik Şartında katılan devletler ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin hakları

da dahil olmak üzere, insan haklarına tam saygı göstermenin ülkesel bütünlüğü ve bağımsızlığı

zayıflatmadığını, tam aksine güçlendirdiğini belirtmişlerdir.55 İstanbul Zirvesi Deklarasyonunda

ise, katılan devletler ulusal azınlıklara mensup kişilerin haklarıyla, özellikle de kültürel kimliklerini etkileyen konularla ilgili yasaları ve politikaları hayata geçirecekleri yönündeki taahhütlerini yinelemişlerdir.56

AGİT bünyesinde azınlık hakları ile ilgili çalışmalar günümüze kadar devam etmekle

birlikte, konuyla ilgili alınan kararlar yukarıda belirtilenlerin tekrarından öteye gitmemiştir.

Yine de AGİT, getirdiği düzenlemelerle ve oluşturduğu denetim sistemiyle günümüzde azınlık

haklarının korunmasında en önemli uluslararası oluşumların başında gelmektedir.57

53. Bölüm III, para. 37.

54. Helsinki Kararları, Bölüm VI, para. 27.

55. “İnsani Boyut” başlığı, Bölüm III.

56. Para. 30.

57. Geçmişten günümüze uluslararası hukukta azınlık haklarıyla ilgili gelişmeler konusunda geniş bilgi için bkz.

Dayıoğlu, op.cit., s. 79-169.

İKİNCİ BÖLÜM:

KUZEY KIBRIS’TA AZINLIKLARLA İLGİLİ MEVZUAT VE UYGULAMALAR

I) Azınlıklarla İlgili İç Hukuk Düzenlemeleri ve Kabul Edilen Uluslararası

Belgeler

Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta uygulanan mevzuatta azınlık haklarıyla ilgili bir düzenleme bulunmadığı gibi, hiçbir azınlık grubu da herhangi bir hukuki statüye sahip değildir. Bu durum normlar

hiyerarşisinin en üstünde bulunan 1985 tarihli KKTC Anayasasında açık bir şekilde görülmektedir. 164 maddeden oluşan ve birçok konuyu düzenlemeyi amaçlayan bir metin olmasına

rağmen Anayasa’da azınlık haklarıyla doğrudan ilgili bir düzenleme yer almamaktadır. Var

olanlar yalnızca negatif haklar getiren dolaylı düzenlemeler niteliğindedir. Azınlık haklarını

koruma altına almaya yönelik pozitif haklara Anayasa metninde yer verilmemiştir.58 Dolayısıyla, KKTC Anayasasında yalnızca ayrımcılığın önlenmesine yönelik düzenlemelerin var olduğu,

azınlıkların korunmasına ilişkin hükümlerin bulunmadığı görülmektedir.59 Negatif haklar getiren ve ayrımcılığın önlenmesini amaçlayan maddeler arasında Anayasa’nın eşitlikle ilgili 8.

maddesi ile “Temel Haklar, Özgürlükler ve Ödevler” başlığını taşıyan İkinci Kısım’da yer alan

birçok maddeyi saymak mümkündür. Başta Anayasa olmak üzere konuyla ilgili mevzuatta var

olan eksiklikleri gidermek amacıyla, yukarıda da belirtildiği gibi, KKTC Cumhuriyet Meclisi 19

Temmuz 2004 tarihli birleşiminde oy birliğiyle Her Türlü Irk Ayrımcılığının Kaldırılması Uluslararası Sözleşmesi ile Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesini kabul edip iç hukukun

bir parçası haline getirmiştir.60 Özellikle Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesinin,

dolayısıyla da 27. maddenin kabulü KKTC yönetimini azınlıkların kimliklerini koruma yönündeki faaliyetlerine karışmama gibi negatif bir tutum almanın yanı sıra, bu yöndeki faaliyetlerini

kolaylaştırıcı önlemler alma konusunda bir de pozitif yükümlülük altına sokmaktadır.61

58. Negatif haklar bir toplumda azınlık-çoğunluk ayrımı yapılmadan herkese tanınan bireysel haklar iken, pozitif

haklar yalnızca çoğunluğa göre dezavantajlı durumda olan azınlık gruplarına mensup kişilere verilen artı haklardır.

Burada bir azınlık grubunun farklı özelliklerini koruması çok güç olduğundan, azınlıklara özel birtakım haklar verilerek çoğunlukla eşitlik sağlanmak istenmektedir. Eşitsiz koşullarda bulunan taraflara eşit kurallar uygulandığı zaman

ortaya eşitsiz sonuçların çıkacağı açıktır. Bu konuda bkz. Rodley, Nigel S., “Conceptual Problems in the Protection

of Minorities: International Legal Developments”, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. XVII, No. 1, (February 1995), s. 50.

Ayrıca bkz. Alfredsson and de Zayas, op.cit., s. 2.

59. Negatif hak-pozitif hak ayrımının bir uzantısı olan ayrımcılığın önlenmesi-azınlıkların korunması ayrımı da azınlık hakları bakımından önemli bir yer tutmaktadır. Buna göre, ayrımcılığın önlenmesi ile azınlıkla çoğunluk arasında

eşitliğin sağlanması amaçlanırken, azınlıkların korunmasında çoğunlukla eşit muamele görmek isteyen, bununla

birlikte temel özelliklerini koruyabilmek amacıyla ayrıca bir de farklı muamele talep eden başat olmayan grupların

korunması amacı söz konusudur. Ayrımcılığın önlenmesi-azınlıkların korunması ayrımı ve bu iki kavramın birbiriyle

ilişkisi için bkz. Oran, Türkiye’de Azınlıklar: Kavramlar, Teori, Lozan, İç Mevzuat, İçtihat, Uygulama, s. 36-37.

60. Söz konusu birleşimde adı geçen sözleşmelerin dışında BM Ekonomik, Sosyal ve Kültürel Haklar Uluslararası

Sözleşmesi, BM Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Sözleşmesine Ek İkinci Seçmeli Protokol ve İşkence ve Diğer Zalimce, İnsanlık Dışı ya da Aşağılayıcı Ceza veya Davranışlara Karşı BM Sözleşmesi de kabul edilen onay yasası ile iç hukuka

aktarılmıştır. Bkz. http://www.cm.gov.nc.tr/Yasalar.aspx, 20.05.2011.

61. “Uluslararası Andlaşmaları Uygun Bulma” başlığını taşıyan KKTC Anayasasının 90/5. maddesine göre usulüne göre yürürlüğe konulmuş uluslararası antlaşmalar yasa hükmünde olup bunlar hakkında Anayasa’ya aykırılık

iddiasıyla Yüksek Mahkeme’ye başvurulamamaktadır. Bu hüküm ile 27. maddenin niteliği göz önünde bulundurulduğunda Anayasa’da konuyla ilgili var olan eksikliğin giderilmeye çalışıldığı görülmektedir. Bununla birlikte, KKTC

Anayasasının 90. maddesinde yapılacak bir değişiklikle yasalar ile temel hak ve özgürlüklere ilişkin uluslararası antlaşma hükümlerinin çatışması halinde uluslararası antlaşmaların esas alınacağının belirtilmesi uluslararası hukuka

uygunluğun sağlanması açısından önemli bir gereklilik olarak karşımıza çıkmaktadır.

25

26

Kişisel ve Siyasal Haklar Uluslararası Sözleşmesine taraf olunmasının ardından,

2007’de başlatılan KKTC Anayasasını değiştirme çalışmaları sırasında azınlık haklarıyla ilgili

bir düzenlemeye yer verme hususu gündeme gelmiştir. Dönemin iktidar partisi Cumhuriyetçi

Türk Partisi-Birleşik Güçler (CTP-BG) konuyla ilgili öneri sunan tek siyasal parti olmuştur. Anayasa taslağının 12/A. maddesinde yer alması öngörülen düzenleme “Devlet, ülkede yaşayan

azınlıkların bu niteliklerinden kaynaklanan haklarını yasa ile koruma altına alır” hükmünü

içermekteydi. Bununla birlikte, 31 Ağustos 2011 itibariyle KKTC Anayasasında herhangi bir

değişiklik yapılmadığından, azınlık haklarıyla ilgili ne CTP-BG’nin önerdiği ne de başka bir düzenleme Anayasa metnine girmiştir.

Mevzuattaki eksikliklere rağmen 31 Temmuz-2 Ağustos 1975 tarihleri arasında Kıbrıslı

Türk ve Rum liderler Rauf R. Denktaş ile Glafkos Klerides arasında Viyana’da yapılan toplumlararası görüşmelerin üçüncü turunda Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta kalan Rumların haklarıyla ilgili alınan

kararlar konumuz açısından önemlidir. Geçerliliğini halen sürdüren, dolayısıyla da Kıbrıs Türk

makamlarını hukuken bağlayan kararlar şu şekildedir: 1) Anlaşma’nın imzalandığı 2 Ağustos

1975 itibariyle Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta bulunan Rumlar burada kalıp kalmama konusunda serbest olacaklardır. Böylece, kuzeyden göç etmeleri konusunda Rumlara herhangi bir baskı uygulanmayacağı Kıbrıs Türk tarafınca kabul edilmiştir; 2) Yine bu tarih itibariyle güneyde yaşayan Kıbrıslı

Rumların bir bölümünün kuzeye transfer edilmesini de kapsayacak şekilde, ailelerin birleştirilmesi ilkesine öncelik tanınacaktır. Böylece, kuzeyde yaşayan Rumların zorla güneye göç ettirilmelerinin yasaklanması bir yana, güneydeki Rumların kuzeyde bulunan ailelerinin yanlarına

gelmelerinin engellenmeyeceği vurgulanmıştır; 3) Anlaşma’nın imzalandığı tarihte Kıbrıs’ın

kuzeyinde bulunan, ancak Güney Kıbrıs’a gitme niyetini taşıyan Kıbrıslı Rumlara herhangi bir

baskı uygulanmadan kendi isteklerine bağlı olarak izin verilecektir; 4) Kuzeydeki Rumlar adanın kuzeyinde serbest dolaşım özgürlüğünden yararlanacaklardır; 5) BM Barış Gücü (UNFICYP)

kuzeydeki Rum köylerine ve ikametgâhlarına serbestçe gidebilecektir; 6) Kendi doktorlarının

tıbbi gözetiminde bulunma, dinlerinin gereklerini yerine getirme ve eğitim olanaklarından yararlanma hususlarını da kapsamak üzere Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta normal bir yaşam sürebilmeleri için

Rumlara her türlü yardım sağlanacaktır.62 Azınlık hakları konusunda mevzuattaki eksikliğe rağmen, Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta yaşayan Rumların hakları bu şekilde güvenceye kavuşturulmuştur.

62. III. Viyana Anlaşması için bkz. http://www.ctpkibris.org/Belgeler/fbelgeler.htm, 28.11.2005.

II) Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta Azınlıklarla İlgili Uygulamalar

A) Hıristiyan Azınlıklar

Yukarıda da değinildiği gibi, bu başlık altında esas olarak kuzeyde yaşayan Kıbrıslı

Rumlarla Marunîler incelenecektir. Rumlarla Marunîleri azınlık olarak tanımladığımız diğer

gruplardan ayıran temel özellik, bu iki grubun Kıbrıslı Türklerden hem dinsel, hem dilsel, hem

de etnik bakımdan farklı oluşlarıdır. Ayrıca, her iki grup da yüzyıllardır Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta yaşayan

“geleneksel azınlıklar”dır. Burada her ne kadar Rumlar ve Marunîleri azınlık olarak değerlendiriyorsak da, yürürlükteki iç ve uluslararası hukuk belgelerine göre bu iki grubun hukuken değil,

fiilen birer azınlık grubu oluşturduklarını bir kez daha belirtmek gerekmektedir.

Rumlarla Marunîleri hukuken azınlık olarak değerlendiremememizin ana nedeni bu

topluluklara mensup kişilere KKTC vatandaşlığının verilmemiş olmasıdır. Vatandaşlık hakkına sahip olup olmadıkları konusunda mevzuat çok net olmamakla birlikte,63 uygulamada bu

insanlar vatandaş sayılmamaktadırlar. Bundan dolayı Rumlarla Marunîler kuzeyde yapılan

cumhurbaşkanlığı, parlamento ve belediye başkanlığı seçimlerine aday veya seçmen olarak

katılamamaktadırlar. Seçme ve seçilme hakkının dışında, vatandaşların yararlandıkları çeşitli

hak ve özgürlüklerden de mahrum kalmaktadırlar.64 Kıbrıslı Türk makamları ise bu kişilerin

istemediklerinden dolayı KKTC vatandaşlığını almadıklarını savunmaktadırlar. Söz konusu kişilere KKTC vatandaşlarından farklı bir kimlik kartı verilmektedir.65

Bu noktada Rumlarla Marunîlere neden KKTC vatandaşlığının verilmediğini sorgulamak gerekmektedir. Bunun en önemli nedeni, Rumlarla Marunîlerin 1974’ten sonra kuzeyde

oluşturulmaya çalışılan homojen Türk ulus-devletinde yabancı ve güvenilir olmayan unsurlar

şeklinde değerlendirilmeleridir. Bundan dolayı, yakın zamana kadar yaşadıkları yerlerden göç