Uploaded by

common.user18742

GC-MS Determination of BADGE and BFDGE in Vegetable Oil

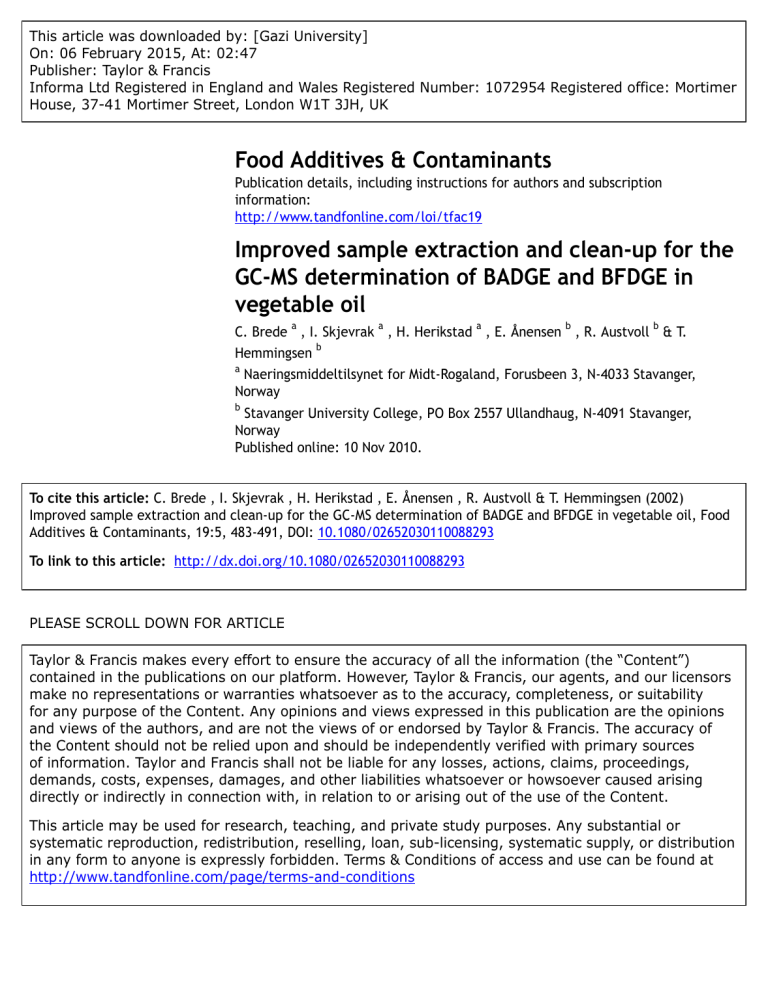

This article was downloaded by: [Gazi University] On: 06 February 2015, At: 02:47 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Food Additives & Contaminants Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tfac19 Improved sample extraction and clean-up for the GC-MS determination of BADGE and BFDGE in vegetable oil a a a b b C. Brede , I. Skjevrak , H. Herikstad , E. Ånensen , R. Austvoll & T. Hemmingsen b a Naeringsmiddeltilsynet for Midt-Rogaland, Forusbeen 3, N-4033 Stavanger, Norway b Stavanger University College, PO Box 2557 Ullandhaug, N-4091 Stavanger, Norway Published online: 10 Nov 2010. To cite this article: C. Brede , I. Skjevrak , H. Herikstad , E. Ånensen , R. Austvoll & T. Hemmingsen (2002) Improved sample extraction and clean-up for the GC-MS determination of BADGE and BFDGE in vegetable oil, Food Additives & Contaminants, 19:5, 483-491, DOI: 10.1080/02652030110088293 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02652030110088293 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions Food Additives and Contaminants , 2002, Vol. 19, No. 5, 483 ± 491 Improved sample extraction and clean-up for the GC-MS determination of BADGE and BFDGE in vegetable oil C. Bredey*, I. Skjevraky, H. Herikstady, E. AÊnensenz, R. Austvollz and T. Hemmingsenz Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 yNñringsmiddeltilsynet for Midt-Rogaland, Forusbeen 3, N-4033 Stavanger, Norway zStavanger University College, PO Box 2557 Ullandhaug, N-4091 Stavanger, Norway (Received 9 April 2001; revised 26 July 2001; accepted 7 August 2001) A straightforwar d method was established for the determination of migration contaminants in olive oil with a special focus on the two can-coating migration compounds bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) and bisphenol F diglycidyl ether (BFDGE). The preferred sample preparation was a single liquid±liquid extraction of compounds from the oil into 20% (v/v) methanol in acetonitrile, followed by clean-up with solid-phase extraction on aminopropy l bonded to silica. This puri®cation procedure selectively removed all free fatty acids from the extracts without removing phenolic compounds of interest. The solid-phas e extraction columns were used many times by implementing a procedure of washing out the strongly retained fatty acids with 2% acetic acid in methanol. Gas chromatography coupled with full scan (m/z 33±700) electron ionization mass spectrometry was used for the determination of several model compounds in olive oil samples. BADGE and BFDGE could be determined in the 0.05±2 mg kg 1 range in oil samples with a relative SD of <6% (six replicates). The method was used in an enforcement campaign for the Norwegian Food Control Authority to analyse vegetable oil samples from canned ®sh-in-oil. Keywords : migration, olive oil, gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, bisphenol A diglycidyl ether, bisphenol F diglycidyl ether, screening method * To whom correspondence should be addressed. e-mail: cato.brede@nmt-mrog.rl.no Introduction Migration of compounds from food-packaging materials to food is a well-known problem. According to EU legislation, such migration is not allowed if it leads to unhealthy concentrations in the food or to unacceptable changes in the composition or organoleptic properties of the food (EEC 1988). Further, EU legislation gives a list of authorized monomers and starting compounds for use in the production of food-contact plastics (EEC 1990). Some of the compounds listed are associated with restrictions, which can be speci®c migration limits (SML). An SML is the maximum allowed concentration of a migrated compound in the food. Another list contains authorized plastic additives. This is still an incomplete list, which means that non-listed substances can also be used today. Nevertheless, the use of other plastic additives must not lead to unhealthy or unacceptable migration levels in the food. Several reports exist on the migration of compounds from can coatings to canned food (Simal-Gandara et al. 1998, Grob et al. 1999, Simoneau et al. 1999a, b, Berger and Oehme 2000, Theobald et al. 2000, Berger et al. 2001). Epoxyphenolic lacquers and organosols are two frequently used can coatings. Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) and bisphenol F diglycidyl ether (BFDGE) are typical candidates of migration from these coatings since they are monomers in the former and might be used as process aids in the latter. Today, BADGE is listed with an SML(T) of 1 mg kg 1 of food, which is a total limit that includes some hydrolysis and chlorination products of BADGE. A similar SML(T) is planned for BFDGE, with the sum of BADGE components added (EEC 2001). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is the preferred technique for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE in food and food simulants (Losada et al. 1991, Biedermann and Grob 1998, Summer®eld et al. 1998, Biles et al. 1999, Simoneau Food Additives and Contaminant s ISSN 0265±203X print/ISSN 1464±5122 online # 2002 Taylor & Francis Ltd http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals DOI: 10.1080/0265203011008829 3 484 C. Brede et al. Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 et al. 1999a, Rauter et al. 1999). It provides robustness and low detection limits partly due to a relatively large sample injection volume. In addition, gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GCMS) can be useful, often to verify a positive result from the HPLC analysis. One paper describes the combination of solid-phase micro-extraction with GC-MS for the determination of BADGE in aqueous food simulants (Salafranca et al. 1999). GC-MS oŒers compound identi®cation based on both retention time and mass spectrum recognition. From a food control perspective, it is important to obtain such conclusive evidence when checking for compliance with the regulations. Many compounds can be expected to migrate from food-contact materials, and testing for compliance provides some challenge to an o cial food control authority. To save time and costs, it is wise to develop generic methods of analysis. One such generic method is the Dutch screening method for potential migrants in food contact plastics (van Lierop 1994, 1997). Similar screening methods should exist also for the analysis of food simulants used in the tests for speci®c migration. GC provides a highly e cient separation of numerous compounds in a single chromatographic run, thus allowing for development of such a generic screening method. In the present work, GC-MS was used for the determination of migration contaminants. Olive oil is one of the EU food simulants and is used to simulate fatty foods in migration experiments. It is de®nitely more complex than aqueous food simulants because it contains free fatty acids and many other compounds in addition to the triglycerides . Free fatty acids usually produce broad peaks in the gas chromatogram, while triglycerides have a low volatility and might be retained in the injector liner or at the column entrance. This puts a high demand on the sample preparation for avoiding interference in the chromatography. Both solid-phase extraction (SPE) and liquid±liquid extraction (LLE) were evaluated for the sample preparation in the present work, aiming to achieve maximum sensitivity, precision and linearity for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE, in addition to the determination of a selection of other model compounds in olive oil. This resulted in an optimized LLE method with SPE clean-up, which was used to determine BADGE and BFDGE in vegetable oil samples from canned ®sh-in-oil products on the Norwegian market. Materials and methods Chemicals Olive oil with speci®cations according to the CEN prestandard ENV 13130-1 was purchased from Norsk Medisinaldepo t (Norway). The following solvents were of analytical grade: acetone, methanol, acetonitrile, dichloromethane and n-hexane (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The following compounds were of analytical or high-purity grade and were used as model compounds: bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (Merck), methyl-tert-butylether (Rathburn, Walkerburn, UK), bisphenol A diglycidyl ether, bisphenol F diglycidyl ether, p-cresol, bisphenol A, 3tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole , hydroquinone (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), butylated hydroxytoluene, dibutylphthalate (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), Irgafos 168, Irganox 1076, Tinuvin 327 (Ciba, Basel, Switzerland), phenol, 2,2 0 -methylenbis(6-tert-butyl4-methylphenol), 2,2 0 -bisphenol F, 4,4 0 -bisphenol F, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, diethylphthalate, benzyl buylphthalate (Aldrich, Milwaukee, MI, USA), 2,4di-tert-butylphenol, 2,6-di-tert-butyl-p-benzoquinone, 1-chloro-dodecane (Acros, New Jersey, USA), di-noctylphthalate (Chem Service, West Chester, USA), acetic acid (Riedel-de Haen Laborchemikalien , Seelze, Germany) and 4,4 0 -di¯uorbenzophenone (Fluorchem, Derbyshire, UK). The bisphenol F diglycidyl ether (BFDGE) was a mixture of equal amounts of the three isomers o,o 0 -BFDGE, o,p 0 BFDGE and p,p 0 -BFDGE, which were assumed to elute on the gas chromatography column in this order. Irgafos 168 phosphate was kindly donated by Borealis, Norway. Sample preparation methods A total of 100 ml standard solutions in acetone or 100 ml neat acetone (sample blanks) were added to 10 g olive oil samples to establish standard curves. A total of 100 ml neat acetone was also added to 10 g samples of vegetable oil from canned ®sh-in-oil. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns (1 g sorbent, 6 ml volume) containing silica, octadecyl bonded to silica (C18) and aminopropyl bonded to silica (NH2 ) were purchased from IST (Mid-Glamorgan, UK). A Supelco-5-7030 vacuum manifold (Supelco, Bellefonte, USA) was used for the SPE. The ¯ow Sample extraction and clean-up for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE rates through the SPE columns were kept at 1± 2 ml min 1 . Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 The optimized sample preparation method based on SPE consisted of the following steps. . Conditioning of the silica SPE column with 5 ml acetone and 5 ml hexane. . Solution of a 0.5 g oil sample in 5 ml hexane. . Application of the sample onto the SPE column. . Washing the SPE column with 5 ml hexane. . Elution of the sample with 5 ml acetone. . Addition of internal standard (1-chloro-dodecane) to the eluate. . Evaporation to dryness at 55°C under a stream of 99.999% nitrogen followed by solving the sample in 1 ml hexane before GC-MS analysis. 485 was a Zebron ZB-5 (Phenomenex, USA) with a 5% phenyl- and 95% methylsiloxane stationary phase of 0.25 mm thickness. The carrier gas was 99.9999% helium (Hydrogass, Norway). Temperature programme: 40°C in 5 min, then programmed 10°C min 1 to 350°C and hold for 15 min. Pressure programme: 7 psi in 2 min during the injection followed by 4 psi in 3 min, then programmed 0.5 psi min 1 to 20 psi and hold for 15 min. Injector temperature: 250°C. Detector temperature: 300°C. The mass spectrometer was a Hewlett-Packard model 5972 mass selective detector operated by the ChemStation software G1701BA v.B.01.00 . Mass spectra were recorded in the full scan mode (m/z 33±700) by using 70 eV electron impact ionization. The optimized sample preparation method based on LLE followed by clean-up with SPE consisted of the following steps. . Addition of 20 mg internal standard (4,4 0 -di¯uorbenzophenone) in 10 ml acetone to a 10 g oil sample contained in a 20 ml glass vial. . Addition of 5 ml 20% (v/v) methanol in acetonitrile to the 10 g oil sample. . Manual shaking of the capped sample vial for 1 min. . Sonication of the sample glass for 10 min followed by resting for 30 min. . Conditioning of the SPE column (C18 or NH2 ) with 4 ml 2% (v/v) acetic acid in methanol (NH2 only), 4 ml methanol, 4 ml acetone and 4 ml acetonitrile, followed by brief drying with vacuum. . Transfer of exactly 3.5 ml of the top solvent phase from the extracted sample to the SPE column. . Elution of the sample followed by washing with 1 ml methanol and collection into a 4 ml glass vial. . Evaporation to dryness at 55°C under a stream of 99.999% nitrogen followed by solving the sample in 1 ml methyl-tert-butylether prior to GC-MS analysis Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry The gas chromatograph was a Hewlett-Packard model 5890 series II (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). 1 ml of each sample was injected in the split-less mode with a Hewlett-Packard model 7673 auto-injector. The 30 m and 0.25 mm i.d. GC capillary column Results and discussion Solid-phase extraction Both LLE and SPE have previously been reported as sample preparation techniques for the determination of BADGE in the olive oil fatty food simulant (EEC 1997). In the present work, SPE was initially evaluated for the extraction of polar and semipolar model compounds from the non-polar triglyceride matrix. When using silica as stationary phase, recoveries of 70±108% were found for BADGE and the three BFDGE isomers (table 1). There is a substantial quantity of extractable compounds in olive oil, including free oleic acid. When using SPE, it is vital that the amount of extractable material does not exceed the capacity of the SPE column. Using SPE on 1 g silica, an olive oil sample of 1 g produced a dried extract of 0.22 g, which is equivalent to 22% of the weight of stationary phase. The extract contained a high amount of oleic acid. Oil samples of diŒerent weights were applied, and the weight of dry extract was plotted against the weight of oil sample (®gure 1). This showed that oil samples >1 g produced extracts of similar weight, indicating a limit of the SPE sample capacity. Hence, a larger amount of stationary phase must be utilized if the sample amount is to be increased. However, this will require larger solvent volumes and was therefore not an option in the present work. 486 C. Brede et al. Table 1. Recoveries for the model compounds extracted from olive oil by using the SPE method (silica column) or by using the LLE-SPE method (NH2 column). Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 Compounds 2,2 0 -Bisphenol F 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol 2,6-di-tert-butyl-p-benzoquinon 4,4 0 -Bisphenol F BADGE; bisphenol A diglycidylether BBP; butyl benzyl phthalate BFDGE; o,o 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BFDGE; o,p 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BFDGE; p,p 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BHA; 3-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole BHT; Butylated hydroxytoluene Bisphenol A BKF; 2,2 0 -methylenbis(6-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol) DBP; dibutyl phthalate DEHA; bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate DEHP; bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate DEP; diethyl phthalate DnOP; di-n-octyl phthalate Hydroquinone Irgafos 168; tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphite Irganox 1076; octadecyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate p-Cresol Phenol Tinuvin 327; 2-(5-chloro-2H-benzotriazol-2-yl)-4,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol Recoveries (%) with SPE method Recoveries (%) with LLE-SPE method n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 70 n.a. 108 87 78 n.a. 4 57 n.a. n.a. 55 51 n.a. n.a. n.a. 0 0 54 n.a. 4 81 21 9 62 42 35 53 55 68 35 11 60 17 33 n.a. 14 44 8 48 0* 5 24 14 n.a. n.a., not applied. *Con®rmed oxidation to Irgafos 168 phosphate. Liquid±liquid extraction Figure 1. Weight of dry SPE extract plotted against weight of olive oil sample. Stationary phase: 1 g 50 ·m silica particles with 60 AÊ pore size. LLE was evaluated for the sample preparation of olive oil samples, initially with a previously reported method for the determination of BADGE in olive oil (EEC 1997). With SPE, it was impractical to use larger sample amounts than 0.5±1 g, which limited the possibility of producing more concentrated samples before GC-MS analysis. With LLE, larger amounts of oil could be applied, leading to higher concentrations of the prepared samples and thus lower detection limits. LLE was performed with mixtures of methanol and acetonitrile. With only 20% (v/v) of methanol added to the acetonitrile, a signi®cant increase in the recovery was observed for polar compounds like bisphenol A and p-cresol compared with using neat acetonitrile. However, methanol concentrations >50% (v/v) resulted in lower recoveries for BADGE and BFDGE. This was either due to a decreased amount of compound transferred Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 Sample extraction and clean-up for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE 487 in the LLE or possibly due to a methanol hydrolysis of BADGE and BFDGE. Methanol hydrolysis of BADGE and BFDGE did not occur when adding 20% (v/v) of methanol to the acetonitrile, as the recoveries for BADGE and BFDGE were unchanged. In addition, the recoveries did not change when using neat acetonitrile and varying the methanol concentration of the washing solvent mixture. Hence, a mixture of 20% (v/v) methanol in acetonitrile was chosen for the extraction of several model compounds from olive oil. The recoveries found for BADGE and the three BFDGE isomers (table 1) were acceptable for quantitative work. Nevertheless, repeated LLE of the same sample is expected to increase the recoveries, but this was not investigated in the present work due to the demand for a quick sample preparation. Clean-up of extracts The dry extract from the LLE weighed only 0.0175 g. This indicated relatively clean samples compared with the samples previously obtained with SPE. It is a common procedure to clean up LLE extracts of fatty samples by using SPE, and often with octadecyl bonded to silica (C18) as stationary phase. C18 was evaluated in the present work but was not found e cient in terms of removing the free fatty acid from the LLE extracts. For this purpose, aminopropyl bonded to silica (NH2 ) was evaluated as the stationary phase, resulting in cleaned-up extracts completely free from fatty acids. Methanol was used for washing the SPE column to elute all of the polar model compounds. Phenolic compounds were completely eluted and could not be found in any of the following column conditioning solvents, as con®rmed by GCMS analysis. Figure 2 shows the total-ion chromatograms of LLE extracts of oil samples from canned tuna ®sh, with clean-up on C18 and with clean-up on NH2 . It was observed that BADGE and the BFDGE isomers elute between 28 and 32 min in these chromatograms, in an area with heavy fatty acid interference when using C18 for clean-up. The immense broadening of the fatty acid peak cannot be avoided when using GC columns with similar non-polar stationary phases. The conditioning procedure implemented into the LLE-SPE method allowed the columns to be used multiple times. All free fatty acid content was washed out of the SPE columns when using 2% acetic acid in Figure 2. Total-ion chromatogram s (TIC) of LLE extracts of oil samples from canned tuna ®sh, with clean-up on C18 (upper) and with clean-up on NH2 (lower). DiŒerent scales of abundances . methanol to promote ion suppressio n of the longchain fatty acids and thereby increasing their solubility in the organic solvent. The e ciency of this column reconditioning was con®rmed by a GC-MS analysis and by weighing of the washing extract. Mass spectrometric detection The MS was operated in the full-scan mode allowing for reconstructed ion chromatograms (RIC) to be made afterwards. For each compound, a RIC was drawn using an ion of high abundance, which resulted in increased selectivity and a lower detection limit. Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 488 C. Brede et al. Figure 3. Overlay of reconstructed ion chromatogram s (RIC) at m/z 181, 197, 312 and 325 showing BADGE and the BFDGE isomers in a cleaned-up LLE extract of olive oil containing 0.5 mg kg 1 of each isomer. This enabled a low level determination of the model compounds in olive oil. o,o 0 -BFDGE, o,p 0 -BFDGE, p,p 0 -BFDGE and BADGE were determined using RICs at m/z 181, 197, 312 and 325 respectively (®gure 3). RICs recorded from an olive oil sample blank did not contain any peaks at the retention times of BADGE and the BFDGE compounds. Mass spectrum recognition by the computer software was successful for these compounds, even at the LOQ (0.05 mg kg 1 ), which provided an additional identi®cation parameter. When olive oil is used as a fatty food simulant, it can contain up to 0.5% free oleic acid. Oleic acid can also be found in vegetable oil samples of canned foods. This acid is a serious interference with the determination of bisphenol A due to close elution on the GC column and because it produces a peak at m/z 213 RIC, which was utilized for the determination of bisphenol A at low levels. By removing free oleic acid as described above, it was possible to obtain higher peak purity for bisphenol A (®gure 4). Bisphenol A and bisphenol F are used in the production of BADGE and BFDGE respectively, and are thus potential migration contaminants in canned foods. It was found that Irgafos 168 is readily oxidized to a phosphate. This was probably the main reason for the absence of Irgafos 168 at m/z 441 RIC. Instead, Irgafos 168 phosphate appeared at m/z 316 and 647 RICs and could be detected at a level corresponding Figure 4. Reconstructed ion chromatogram s (RIC) at m/z 213 of LLE extracts of olive oil samples containing 1 mg kg 1 bisphenol A, with clean-up on C18 (upper) and with clean-up on NH2 (lower). to 0.5 mg kg 1 Irgafos 168 in olive oil. The mass spectrum and retention time of Irgafos 168 phosphate was con®rmed by injections of a standard solution. Analytical characteristics In this work, the limit of detection (LOD) was de®ned as the amount of compound to give a signal-to-noise ratio of 2. With the SPE method, and with full-scan GC-MS analysis, the LOD for BADGE and the BFDGE isomers were close to 1 mg kg 1 olive oil. By using selected-ion monitoring (SIM) at abundant ions, it was possible to reduce the LODs by a factor Sample extraction and clean-up for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE 489 Table 2. Limits of detection (S/N = 2) for the model compounds in olive oil samples using the LLE-SPE method. Limits of detection (mg kg 1 olive oil) Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 Compounds 2,2 0 -bisphenol F 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-p-benzoquinon 4,4 0 -Bisphenol F BADGE; bisphenol A diglycidylether BBP; butyl benzyl phthalate BFDGE; o,o 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BFDGE; o,p 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BFDGE; p,p 0 -bisphenol F diglycidylether BHA; 3-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole BHT; butylated hydroxytoluene Bisphenol A BKF; 2,2 0 -methylenbis(6-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol) DBP; dibutyl phthalate DEHP; bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate DEP; diethyl phthalate DnOP; di-n-octyl phthalate Hydroquinone Irgafos 168; tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphite Irganox 1076; octadecyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate p-Cresol Phenol 0.1 0.01 0.09 0.01 0.01 0.04 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.05 0.01 0.03 0.06 0.5* 0.5 0.03 0.01 *Determined as the Irgafos 168 phosphate. of 10. However, with GC-MS in the SIM mode, it was impossible to identify the compounds by mass spectrum recognition, but only by retention times. Interference might exist in vegetable oil extracts from canned ®sh, making the SIM approach less favourable. by adjusting the extraction solvent polarity. Future work will explore the usefulness of the method for migration testing of materials and articles in contact with the olive oil food simulant. With the combined LLE±SPE method, and with fullscan GC-MS analysis, substantially lower LODs were observed (table 2). Especially the LODs for BADGE and BFDGE were low enough for compliance testing, giving limits of quantitation (LOQ) of 0.05 mg kg 1 olive oil. Six consecutive injections of prepared samples from olive oil containing 1 mg kg 1 BADGE and the BFDGE isomers produced relative SDs <6%. The same level of precision was found by injecting six extracted samples containing phthalates (DEP, DBP, BBP, DEHP, DnOP). Linear standard curves (R2 = 0.995±0.999) were obtained for BADGE and the BFDGE isomers in the 0.05± 2 mg kg 1 range. Real samples For some compounds, higher recoveries will be required for the method to provide reliable quantitative data for diŒerent vegetable oil samples. This might be achieved by performing repeated LLE per sample or Real samples of vegetable oil from canned ®sh in oil were analysed as part of an enforcement campaign for the Norwegian Food Control Authority. Cans of 17 diŒerent products were collected, which were mostly tuna ®sh and sardines. The cans were weighed before and after drainage of the oil, and also after removing the ®sh meat. The relative amount of oil in a product was estimated and used for calculating the speci®c migration level of BADGE and BFDGE in the food. The amount of BADGE and BFDGE in ®sh meat was set to zero. This simpli®cation was possible because ®sh meat is likely to contain 20 times lower amounts of BADGE and BFDGE than the oil (Summer®eld et al. 1998). In addition, the reaction products for BADGE and BFDGE were not determined to simplify the analysis. Thus, with the current C. Brede et al. 490 Table 3. Levels of BADGE and BFDGE found in samples of canned ®sh-in-oil. All samples originated from diŒerent cans, but equal numbers represent the same product. Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 Total concentration of Concentration of BFDGE in the food BADGE in the food Sample number (mg kg 1 ) (mg kg 1 ) 1A 1B 1C 1D 2A 2B 2C 2D 3A 3B 3C 0.416 0.457 0.564 0.587 0.233 0.813 0.622 0.537 0.569 0.863 0.982 0.017 0.018 0.023 0.024 0.009 0.03 0.025 0.021 0.023 0.03 0.04 n.d. n.d. 0.006 0.001 0.006 0.001 n.d. 0.032 0.002 n.d. n.d. 0.013 0.001 0.008 0.001 0.007 0.001 selective MS detection. The GC-MS method developed here was suitable for the determination of the can-coating migration contaminants BADGE and BFDGE in vegetable oil. On the Norwegian market, three of 17 products of canned ®sh-in-oil contained BFDGE and traces of BADGE, but at total levels <1 mg kg 1 in the food. Hence, no evidence of noncompliance was found. The established method can be applied for screening of several migration contaminants in vegetable oil, and might prove to be useful for migration testing of materials and articles in contact with the olive oil food simulant. However, for some compounds, higher recoveries must be achieved to provide reliable quantitative data. Acknowledgements method, any evidence of non-compliance could only be obtained be revealing levels of BADGE and BFDGE above the limit. Three products contained BFDGE in all cans and traces of BADGE in some cans (table 3). The variation within cans of the same product was large, as indicated by 16±44% relative SD (BFDGE). The levels of BADGE in some of the cans were close to the detection limit of the method and signi®cantly lower than the levels of BFDGE. The total levels of BADGE and BFDGE were always <1 mg kg 1 food, and thus no evidence of noncompliance with the current legislation was found in the present work. No analyses of the can lacquers were performed. However, information was received from the manufacturer of one canned product which was found to contain BFDGE and traces of BADGE. This information revealed that the can had an organosol lacquer inside the body and an epoxyphenolic lacquer inside the lid. Conclusions Compared with SPE, the LLE method followed by clean-up with SPE gave the lowest detection limits for the model compounds in prepared olive oil samples. The optimized sample preparation produced an extract free from fatty acid content which otherwise can be a major interference in GC, even when using a The authors thank their Project Coordinator Turid Hellstrùm, Norwegian Food Control Authority, for the funding of the work. References Berger, U., and Oehme, M., 2000, Identi®cation of derivatives of bisphenol A diglycidyl ether and novolac glycidyl ether in can coatings by liquid chromatography/ion trap mass spectrometry. Journal of the Association of O cial Analytical Chemists, 83, 1367±1376. Berger, U., Oehme, M., and Girardin, L., 2001, Quanti®cation of derivatives of bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) and novolac glycidyl ether (NOGE) migrated from can coatings into tuna by HPLC/¯uorescence and MS detection. Fresenius Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 369, 115±123. Biedermann, M., and Grob, K., 1998, Food contamination from epoxy resins and organosols used as can coatings: analysis by gradient NPLC. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 15, 609±618. Biles, J. E., White, K. D., and McNeal, T. P., 1999, Determination of the diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A and its derivatives in canned foods. Journa l of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 47, 1965±1969. EEC, 1988, Council Directive of 21 December 1988 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to materials and articles intended to come into contact with foodstuŒs (89/109/ EEC). O cial Journa l of the European Communities, L40, 38. EEC, 1990, Commission Directive of 23 February 1990 relating to plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foodstuŒs (90/128/EEC). O cial Journal of the European Communities, L75, 19. EEC, 1997, Development of methods of analysis for monomers and other starting substances with SML and/or QM limits in directives 90/128/EEC and 92/39/EEC. Downloaded by [Gazi University] at 02:47 06 February 2015 Sample extraction and clean-up for the determination of BADGE and BFDGE EEC, 2001, Draft Commission Directive on the use of some epoxy derivatives in materials and articles intended to come into contact with foodstuŒs (SANCO/2001/0336). Grob, K., Spinner, C., Brunner, M., and Etter, R., 1999, The migration from the internal coatings of food cans summary of the ®ndings and call for more eŒective regulation of polymers in contact with foods: a review. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 16, 579±590. Losada, P. P., Mahia, P. L., Oderiz, L. V., Lozano, J. S., and Gandara, J. S., 1991, Sensitive and rapid reversed-phase liquid chromatography-¯uorescence method for determining bisphenol A diglycidyl ether in aqueous-based food simulants. Journal of the Association of O cial Analytical Chemists, 74, 925±928. Rauter, W., Dickinger, G., Zihlarz, R., and Lintschinger , J., 1999, Determination of Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) and its hydrolysis products it canned oily foods from the Austrian market. Zeitschrift fur Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und -Forschung A, 208, 208±211. Salafranca, J., Batlle, R., and Nerin, C., 1999, Use of solid-phase microextraction for the analysis of bisphenol A and bisphenol A diglycidyl ether in food simulants, Journa l of Chromatography A, 864, 137±144. Simal-Gandara, J., Paz-Abuin, S., and Ahrne, L., 1998, A critical review of the quality and safety of BADGE-based epoxy coat- 491 ings for cans: implications for legislation on epoxy coatings for food contact. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 38, 675±688. Simoneau, C., Theobald, A., Hannaert, P., Roncari, P., Roncari, A., Rudolph, T., and Anklam, E., 1999a, Monitoring of bisphenol-A-diglycidyl-ether (BADGE) in canned ®sh in oil. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 16, 189± 195. Simoneau, C., Theobald, A., Wiltschko, D., and Anklam, E, 1999b, Estimation of intake of bisphenol-A-diglycidyl-ether (BADGE) from canned ®sh consumption in Europe and migration survey. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 16, 457±463. Summerfield, W., Goodson, A., and Cooper, I., 1998, Survey of Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) in canned foods. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 15, 818±830. Theobald, A., Simoneau, C., Hannaert, P., Roncari, P., Roncari, A., Rudolph, T., and Anklam, E., 2000, Occurrence of bisphenol-F-diglycidyl ether (BFDGE) in ®sh canned in oil. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 17, 881±887. Van Lierop, J. B., 1994, Enforcement of European Community legislation at the national level. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 11, 131±139. Van Lierop, J. B., 1997, Enforcement of food packaging legislation. Food Additives and Contaminant s, 14, 555±560.