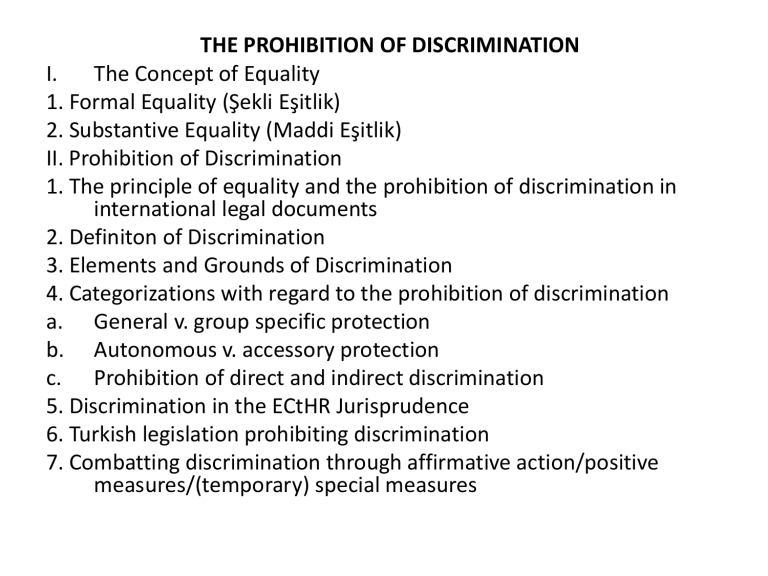

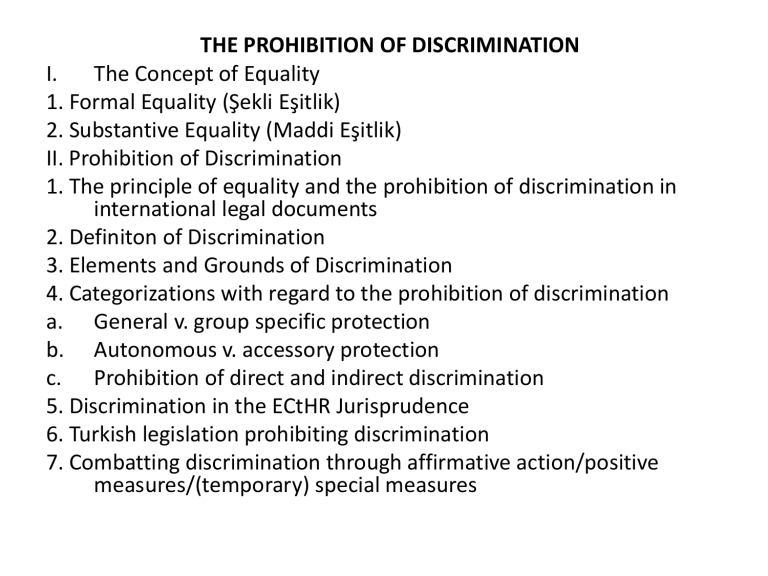

THE PROHIBITION OF DISCRIMINATION

I.

The Concept of Equality

1. Formal Equality (Şekli Eşitlik)

2. Substantive Equality (Maddi Eşitlik)

II. Prohibition of Discrimination

1. The principle of equality and the prohibition of discrimination in

international legal documents

2. Definiton of Discrimination

3. Elements and Grounds of Discrimination

4. Categorizations with regard to the prohibition of discrimination

a. General v. group specific protection

b. Autonomous v. accessory protection

c. Prohibition of direct and indirect discrimination

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

6. Turkish legislation prohibiting discrimination

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

Preliminary Question: Why is the principle of non-discrimination vital for

the protection of human rights, and thus, for our lecture?

•The prohibition of discrimination is the negative restatement of the

principle of equality.

•The universality of human rights is based on the premise that all people

are born “free and equal in dignity and rights”.

UDHR (1948), Preamble: “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity

and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human

family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,…”

Art. 1: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and

rights.They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act

towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

•Equality is the cornerstone of all democratic States – equality of

persons before the law, equality of opportunity, equality of access to

education

•Principle of equality and the prohibition of discrimination is the

precondition for all other human rights to be applied effectively.

• A perspective regarding the status of men and women:

http://fgulenyazilari.blogcu.com/kadin-erkek-birbirine-esitmidir/3224062

• To say that human beings are equal is not to say they are identical.

The postulate of equality implies that underneath apparent

differences, certain recognizable entities or units exist that, by dint of

being units, can be said to be ‘equal.’ (Thomson 1949, p. 4).

Fundamental equality means that persons are alike in important

relevant and specified respects alone, and not that they are all

generally the same or can be treated in the same way (Nagel 1991). In

a now commonly posed distinction, stemming from Dworkin (1977, p.

370), moral equality can be understood as prescribing treatment of

persons as equals, i.e., with equal concern and respect, and not the

often implausible principle of treating persons equally. This

fundamental idea of equal respect for all persons and of the equal

worth or equal dignity of all human beings (Vlastos 1962) is accepted

as a minimal standard by all leading schools of modern Western

political and moral culture. Any political theory abandoning this notion

of equality will not be found plausible today. moral equality

constitutes the ‘egalitarian plateau’ for all contemporary political

theories (Kymlicka 1990, p.5).

I.

The Concept of Equality

1. Formal Equality:

•Formal equality simply suggests that likes must be treated alike, a principle

that Aristotle formulated in reference to Plato (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics,

V.3. 1131a10-b15; Politics, III.9.1280 a8-15, III. 12. 1282b18-23). So, “equality

before the law” means first and foremost that the law should apply to all

persons in an equal and consistent manner (EU Charter, Justice Commentary).

•This approach is reflected in the concept of less favourable treatment, namely,

direct discrimination.

Şekli eşitlik: Herkesin, tüm verili koşullarıyla eşit olduğu varsayımından yola

çıkan, eşit durumda olanların eşit muamele görmesini ve ayrımcılık yapılmadığı

sürece mevcut durumun korunmasını eşitliğin varlığı için yeterli sayan eşitlik

anlayışı. (Ayrımcılık Yasağı, Gül ve Karan, s. 6)

•This formal principle is reasoned with two different perspectives: a specific

application of a rule of rationality, and a moral principle of justice, basically

corresponding with acknowledgement of the impartial and universalizable

nature of moral judgments. So what matters is not the consistency with one’s

subjective demands, a possible justification of the equal or unequal treatment

vis-à-vis others should be made, and the treatment should be evaluated on the

situation’s objective features. (Stanford Ensyclopedia of Philosophy)

Q: Any defects of this approach? Does an equal treatment always purport to an

equal outcome?

2. Substantive equality (Moral Equality):

•Until the eighteenth century, it was assumed that human beings are unequal

by nature and therefore, that there was a natural human hierarchy. This

understanding collapsed with the advent of the idea of natural right and its

assumption of an equality of natural order among all human beings. This idea

was accompanied by the presumption that everyone deserved the same

dignity and the same respect. This proposition gave birth to the widely held

conception of substantive, universal, moral equality.

•A legal approach: ‘Substantive equality’ is a conception of equality that is

concerned with the ensuring ability of persons to compete on an equal basis,

having regard to various obstacles that may impede this equality of

opportunity.

•Substansive equality is a departure from classic or formal equality (or treating

likes alike) and from equal treatment (ensuring that laws or policies apply to

everyone in the same way). Substantive equlity is concerned that laws and

customary practices do not diminish anyone’s access to societal goods or

perpetuate discrimination. The aim of substantive equality analysis is to use

law to remedy past and present disadvantage by examining the context or

“lived-experiences” of those to whom equality in result is due.

Maddi Eşitlik: Kişi ve kişi grupları arasındaki farklılıkları olumlu yönde göz

önünde bulunduran ve onları eşit veya aynı varsaymayan eşitlik anlayışı. Bu

sayede mevcut eşitsizlikleri ortadan kaldırmak için geçici özel önlemler gibi

önlemler gündeme gelebilmektedir. (Gül, Karan, s. 7)

(See slides on Affirmative Action)

2. Substantive Equality

• In particular, claims of ‘substantive equality’ seek to

highlight significant social obstacles (particularly

discrimination based on social characteristics) to equal

access to such goods as education, employment, goods

and services.

• For instance, an unequal distribution of childcare

responsibilities between women and men may make it

more difficult for women with children to undertake jobs

with long working hours without additional support or

accommodation. Accordingly, merely eliminating sex

discrimination on the hiring stage may not be enough to

ensure that female workers have the same employment

opportunities as male workers. It suggests that it may be

necessary to take further steps to accommodate or assist

female workers with children so that they may compete

on equal terms with their male counterparts.

• More on the significance of the principle of equality for human rights:

excerpts from the South West Africa Case before the ICJ (Ethiopia v. South

Africa; Liberia v. South Africa, 18 July 1966) and the Dissenting opinion of

Judge Tanaka:

“ Examining the principle of equality before the law, we consider that it is

philosophically related to the concepts of freedom and justice. The freedom

of individual persons, being one of the fundamental ideas of law, is not

unlimited and must be restricted by the principle of equality allotting to each

individual a sphere of freedom which is due to him. In other words the

freedom can exist only under the premise of the equality principle. In what

way is each individual allotted his sphere of freedom by the principle of

equality? What is the content of this principle? The principle is that what is

equal is to be treated equally and what is different is to be treated differently,

namely proportionately to the factual difference. This is what was indicated

by Aristotle as justitia commutativa and justitia distributiva.

The most fundamental point in the equality principle is that all human beings

as persons have an equal value in themselves, that they are the aim itself and

not means for others, and that, therefore, slavery is denied. The idea of

equality of men as persons and equal treatment as such is of a metaphysical

nature. It underlies all modern, democratic and humanitarian law systems as

a principle of natural law. This idea, however, does not exclude the different

treatment of persons from the consideration of the differences of factual

circurmstances such as sex, age, language, religion, economic condition,

education, etc. To treat different matters equally in a mechanical way would

be as unjust as to treat equal matters differently.” (p. 303)

“We can say accordingly that the principle of equality before the law does not

mean the absolute equality, namely equal treatment of men without regard to

individual, concrete circumstances, but it means the relative equality, namely

the principle to treat equally what are equal and unequally what are unequal.

The question is, in what case equal treatment or different treatment should

exist. If we attach importance to the fact that no man is strictly equal to

another and he may have some particularities, the principle of equal

treatment could be easily evaded by referring to any factual and legal

differences and the existence of this principle would be virtually denied. A

different treatment comes into question only when and to the extent that it

corresponds to the nature of the difference. To treat unequal matters

differently according to their inequality is not only permitted but required. The

issue is whether the difference exists. Accordingly, not every different

treatment can be justified by the existence of differences themselves, namely

that which is called for by the idea of justice –‘the principle to treat equal

equally and unequal according to its inequality, constitutes an essential

content of the idea of justice’ (Goetz Hueck, Der Grundsatz der

Gleichmeassigen Behandlung in Privatrecht, 1958, p. 106).”

“…the principle of equality being in the nature of natural law and therefore of

a supra-constitutional character, is placed at the summit of hierarchy of the

system of law, and all positive laws including the constitution shall be in

conformity with this principle.” (p. 304)

1.

II. Discrimination

The principle of equality and the prohibition of discrimination in international

legal documents

UN CHARTER

PREAMBLE

“WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS DETERMINED…. to reaffirm faith in

fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the

equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and…”

CHAPTER I: PURPOSES AND PRINCIPLES

Article 1

“The Purposes of the United Nations are: …

2. To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of

equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures

to strengthen universal peace;

3.

To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an

economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging

respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to

race, sex, language, or religion; and…”

Other Articles : Art. 8 (equality), Art. 13, 55, 76 (without distinction to…)

1.

The principle of equality and the prohibition of discrimination in

international legal documents

UN INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS

Article 26

All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any

discrimination to the equal protection of the law. In this respect, the law shall

prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective

protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex,

language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property,

birth or other status.

Madde 26

Herkes yasa önünde eşittir ve herhangi bir ayrımcılık gözetilmeksizin

yasanın eşit şekilde koruması hakkına sahiptir. Bu bağlamda, yasa herhangi bir

ayrımcılığı yasaklayacak ve ırk, renk, cinsiyet, dil, din, siyasal ya da diğer görüş,

ulusal ya da toplumsal köken, mülkiyet, doğum ya da başka bir statü gibi

herhangi temeldeki bir ayrımcılığa karşı tüm kişilerin etkili ve eşit biçimde

korunmasını güvence altına alacaktır.

*In the official translation, “ayrım gözetilmeksizin” is used, although it is seen

that Art. 2 and Art. 25 uses the wording “distinction”; whereas this article uses

“discrimination”. The official translation neglects the difference in the wording

of the articles.

1. The principle of equality and the prohibition of

discrimination in international legal documents

Other Conventions entailing the prohibition of discrimination:

• Genocide Convention (1948)

• Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951)

• International Convention relating to the Status of Stateless

Persons (1954)

• International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment

of the Crime of Apartheid (1973)

• Additional Protocol (1977) to the Geneva Conventions on the

Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts

• The Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or

Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984),

• International Convention against Apartheid in Sports (1985)

• Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)

2.

Definition of Discrimination

•

At its core, discrimination is “treating differently, without an objective and

reasonable justification, persons in relevantly similar situations” (ECtHR, Willis v.

UK, 2002, para 48; Zarb Adami v. Malta, 20.06.2006)

- International law conceptualizes discrimination as unjustified debasement of

individuals on the grounds of identity-related characteristics and embodies several

approaches and categories of prohibitions to discriminate.

Legal definitons of discrimination:

•International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial

Discrimination(1965):

Art.1: In this Convention, the term "racial discrimination" shall mean any distinction,

exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic

origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition,

enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms

in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

Madde 1: Bu Sözleşmede “ırksal ayrımcılık” terimi, siyasi, ekonomik, sosyal, kültürel

alanda ya da kamusal yaşamın herhangi bir başka alanında, eşitlik temelinde olarak,

insan haklarının ve temel özgürlüklerin tanınmasını, bunlardan yararlanılmasını yahut

bunların kullanılmasını kaldırmak yahut zayıflatmak amacını taşıyan ya da etkisini

doğuran (ve) ırk, renk, soy ya da ulusal yahut etnik kökene dayanan herhangi bir farklılık

gözetme, dışlama, kısıtlama yahut öncelik tanıma/tercihte bulunma anlamına gelecektir.

2. Definition of Discrimination

• Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

(1979):

Art. 1:

For the purposes of the present Convention, the term "discrimination

against women" shall mean any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on

the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the

recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital

status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and

fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any

other field.

Madde 1:

Bu Sözleşmenin amaçları bakımından “kadınlara karşı ayrımcılık” terimi,

kadınların medeni durumları her ne olursa olsun, siyasal, ekonomik, sosyal,

kültürel, medeni ya da herhangi bir başka alanındaki insan haklarının ve

temel özgürlüklerin, erkekler ve kadınlar arasında eşitlik temelinde olarak,

kadınlara tanınmasını, kadınlar tarafından bunlardan yararlanılmasını yahut

kullanılmasını zayıflatma (azaltma) yahut hükümsüz kılma etkisini doğuran ya

da bu amaca yönelen, cinsiyete dayalı herhangi bir farklılık gözetme, dışlama,

ya da kısıtlama anlamına gelecektir.

3. Elements and Grounds of Discrimination in International Legal

Documents:

•Elements:

1. Distinction (farklılık gözetme)

2. Exclusion (dışlama)

3. Restriction (kısıtlama/sınırlama)

4. Preference (öncelik tanıma)

•Grounds (see suspect qualifications)

-race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national

or social origin, property, birth or other status (ICCPR art. 2/1, art. 26;

ICESCR art. 2/2)

-race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin (IAOKS, art. 1)

-economic condition – inter alia- (UNESCO, Conv. Against Discrim. in

Education)

-disability –inter alia- (Convention on the Rights of the Child)

Q: Is there a hierarchy among these grounds?

4. Categorizations with regard to the prohibition

of discrimination

a. General v. group specific protection: Group specific prohibitions of

discrimination are applicable to particular categories of persons. E.g.

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination,

CEDAW, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2006, ILO

Conventions

b. Autonomous v. accesory protection

Art. 26 of the ICCPR is the only provision of a universal treaty that affords this

form of autonomus all-embracing protection against discrimination. 14th Article

of the ECHR suggests an accessory protection, whereas the 12th Protocol of the

ECHR provides an autonomous protection at the regional level.

PROTOCOL 12, ARTICLE 1

General prohibition of discrimination

1. The enjoyment of any right set forth by law shall be secured

without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour,

language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social

origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or

other status.

2. No one shall be discriminated against by any public authority

on any ground such as those mentioned in paragraph 1.

Ayrımcılığın genel olarak yasaklanması

1. Hukuken temin edilmiş olan tüm haklardan yararlanma,

cinsiyet, ırk, renk, dil, din, siyasi veya diğer kanaatler, ulusal ve

sosyal köken, ulusal bir azınlığa mensup olma, servet, doğum

veya herhangi bir diğer statü bakımından hiçbir ayrımcılık

yapılmadan sağlanır.

2. Hiç kimse, 1. paragrafta belirtildiği şekilde hiçbir gerekçeyle,

hiçbir kamu makamı tarafından ayrımcılığa maruz bırakılamaz.

ARTICLE 14

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set

forth in this Convention shall be secured without

discrimination on any ground such as sex, race,

colour, language, religion, political or other opinion,

national or social origin, association with a national

minority, property, birth or other status.

Ayrımcılık yasağı

Bu Sözleşme'de tanınan hak ve özgürlüklerden

yararlanma, cinsiyet, ırk, renk, dil, din, siyasal veya

diğer kanaatler, ulusal veya toplumsal köken, ulusal

bir azınlığa aidiyet, servet, doğum başta olmak üzere

herhangi başka bir duruma dayalı hiçbir ayrımcılık

gözetilmeksizin sağlanmalıdır.

c. Direct v. indirect discrimination

•Direct discrimination occurs where an adverse

distinction in legislation or in the application of a

basically non-discriminatory law is directly related to

one of the prohibited grounds of distinction without

adequate objective justification.

•Doğrudan ayrımcılık: Burada aynı veya benzer

konumdaki kişilerden biri veya bir kısmı bakımından

daha olumsuz sonuçlar yaratan veya böyle bir

sonucun ortaya çıkması ihtimalini doğuran farklı

muameleler söz konusudur.

•http://web.hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n=turkeymust-take-action-over-lgbt-discrimination-ai-reportsuggests-2011-06-20

c. Direct v. indirect discrimination

•Indirect discrimination: Laws or their application may result in

distinctions that, though unrelated to any prohibited grounds,

in practice have detrimental effects that exclusively or at least

disproportionately affect people with such characteristics.

•“A general policy or measure that has disproportionately

prejudicial effects on a particular group may be considered

discriminatory notwithstanding that it is not specifically aimed

at that group … and that discrimination potentially contrary to

the Convention may result from a de facto situation.” (ECtHR,

D.H. and others v. Czech Republic, 7.2.2006)

•Dolaylı ayrımcılık: Herkes için aynı şekilde geçerli ve görünüşte

tarafsız olan, ancak bazı kişi ve gruplar üzerinde diğerlerinden

farklı olarak veya diğer gruplardan daha fazla olumsuz etkiler

yaratan yasal düzenleme, uygulama ve tedbirler.

Q: Why do we even make this distinction?

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

Steps pursued by the Court to decide on the

violation of Article 14

①Designating the Convention article whose ambit

Article 14 falls within

②Deciding whether there was a difference of

treatment between the applicant and others

③Deciding if these persons were in ‘analogous

situations’

④Deciding whether there is an objective and

reasonable justification for the difference of

treatment (add. to the formulation: pursuing a

legitimate aim, proportionality relationship between

the means employed to the aim pursued) (see

Rasmussen v. Denmark (28.11.1984))

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

①The ambit test:

In terms of the parasitic nature of the article, there is no need to show or

claim violation of another article, ‘falling within the ambit of a Convention

right’ suffices. This is called the “ambit test approach”.

see Belgian Linguistic Case (23.07.1968):

“In its opinion of 24th June 1965, the Commission expressed the view that

although Article 14 (art. 14) is not at all applicable to rights and freedoms not

guaranteed by the Convention and Protocol, its applicability "is not limited to

cases in which there is an accompanying violation of another Article". In the

view of the Commission "such a restrictive application" would conflict with the

principle of effectiveness established by the case law of the Permanent Court

of International Justice and the International Court of Justice, for the

discrimination would be limited to the aggravation "of the violation of another

provision of the Convention…”

If a State goes beyond its obligation under a Convention right, it has to do

this in a non-discriminatory manner. (textbook, p. 548)

Egs. Right to adopt is not protected under art. 8, however, French law enables

single persons to adopt, so what if a single homosexual is denied adoption?

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

Case of E.B. v. France (2008):

“91. The Court reiterates that, for the purposes of Article 14, a

difference in treatment is discriminatory if it has no objective

and reasonable justification, which means that it does not

pursue a “legitimate aim” or that there is no “reasonable

proportionality between the means employed and the aim

sought to be realised” (see, inter alia, Karlheinz Schmidt, cited

above, § 24; Petrovic, cited above, § 30; and Salgueiro da Silva

Mouta, cited above, § 29). Where sexual orientation is in issue,

there is a need for particularly convincing and weighty reasons

to justify a difference in treatment regarding rights falling

within Article 8 (see, mutatis mutandis, Smith and Grady v. the

United Kingdom, nos. 33985/96 and 33986/96, § 89, ECHR

1999-VI; Lustig-Prean and Beckett v. the United Kingdom, nos.

31417/96 and 32377/96, § 82, 27 September 1999; and S.L. v.

Austria, no. 45330/99, § 37, ECHR 2003-I).”

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

②Differential treatment on a prohibited ground:

- The list is not exhaustive.

The difference of treatment has to be explained in terms

of personal characteristics – What is precisely meant

by personal characteristic is not always easy to

determine. Eg. The Court did not accept the

geographical location where the applicant was

detained (Magee v. UK at O’Boyle, p. 585); residence of

a person, like nationality, however, falls within the

scope of this (Carson and others v. UK in textbook, p.

551)

• Examples of “other status”: sexual orientation, marital

status, country of domicile or residence, the suffering

from the psychological harm caused by child abuse”

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

③Being in similar situations

The Court often passes this step and starts

discussing whether there can be a justification for

the differentiation.

•Persons whose situations are significantly

different should be treated differently. Eg.

Thlimmenos v. Greece, 6.5.2000 – a Jehova’s

witness being convicted because of not serving in

the army and excluded from a profession as a

result

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

④ Objective and reasonable justification

Unless there is a common European standard, the

Court will less probably condemn the differentiation.

Eg. Rasmussen v. Denmark (28.11.1984):

“The scope of the margin of appreciation will vary

according to the circumstances, the subject-matter

and its background; in this respect, one of the

relevant factors may be the existence or nonexistence of common ground between the laws of

the Contracting States.” (para. 40)

See Sidabras and Dziautas v. Lithuania (7.5.2005) –

the KGB agents case - here there was no reasonable

justification as to the different treatment.

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

Intensive scrutiny of differential treatment for

‘suspect categories’

• Very weighty reasons are required to justify the

different treatment, and the margin of

apprication of the State is pretty narrow in

terms of some grounds, as observed in the

ECtHR jurisprudence. There grounds are:

- Race or ethnic origin, nationality, sex,

legitimacy, religion

5. Discrimination in the ECtHR Jurisprudence

• Racial discrimination

- The Court has indicated that discrimination on grounds of ethnicity is a form

of racial discrimination – see Secic v. Croatia: A Croatian of Roma origin who

was attacked and injured, where his attackers shouted at him assaulting his

ethnic origin while attacking him.

• Minorities and discrimination:

- DH v. Czech Republic (13.11.2007) : Special schools where predominantly

kids of Roma origin attend – violation of Art. 14 in conjunction with Art. 2 of

Protocol 1.

• Discrimination based on sexual orientation

- Smith and Grady v. UK (27.9.1999) constitutes a landmark case.

- The first time right after this case, where the Court found a violation of Art.

14 in conjunction with Art. 8 in terms of sexual orientation is Salguiero da

Silva Mauta v. Portugal (21.12.1999) – rejection of awarding parental

responsibility to the father, his homosexuality being a decisive factor

- Another important eg. İs EB v. France, where a lesbian was denied from

adoption as a single mother.

6. Turkish Legislation Prohibiting Discrimination

ANAYASA

X. Kanun önünde eşitlik

MADDE 10- Herkes, dil, ırk, renk, cinsiyet, siyasî düşünce, felsefî inanç,

din, mezhep ve benzeri sebeplerle ayırım gözetilmeksizin kanun

önünde eşittir.

(Ek fıkra: 7/5/2004-5170/1 md.) Kadınlar ve erkekler eşit haklara sahiptir.

Devlet, bu eşitliğin yaşama geçmesini sağlamakla yükümlüdür. (Ek

cümle: 12/9/2010-5982/1 md.) Bu maksatla alınacak tedbirler eşitlik

ilkesine aykırı olarak yorumlanamaz.

(Ek fıkra: 12/9/2010-5982/1 md.) Çocuklar, yaşlılar, özürlüler, harp ve

vazife şehitlerinin dul ve yetimleri ile malul ve gaziler için alınacak

tedbirler eşitlik ilkesine aykırı sayılmaz.

Hiçbir kişiye, aileye, zümreye veya sınıfa imtiyaz tanınamaz.

Devlet organları ve idare makamları bütün işlemlerinde kanun önünde

eşitlik ilkesine uygun olarak hareket etmek zorundadırlar. (*)

* 9/2/2008 tarihli ve 5735 sayılı Kanunun 1 inci maddesiyle; bu fıkraya

“bütün işlemlerinde” ibaresinden sonra gelmek üzere “ve her türlü

kamu hizmetlerinden yararlanılmasında” ibaresi eklenmiş ve bu ibare

Anayasa Mahkemesinin 5/6/2008 tarihli ve E.: 2008/16, K.: 2008/116

sayılı Kararı ile iptal edilmiştir. (R.G.: 22/10/2008, 27032)

6. Turkish Legislation Prohibiting Discrimination

TCK

Adalet ve kanun önünde eşitlik ilkesi

MADDE 3.

(1) Suç işleyen kişi hakkında işlenen fiilin ağırlığıyla

orantılı ceza ve güvenlik tedbirine hükmolunur.

(2) Ceza Kanununun uygulamasında kişiler arasında

ırk, dil, din, mezhep, milliyet, renk, cinsiyet, siyasal

veya diğer fikir yahut düşünceleri, felsefi inanç,

millî veya sosyal köken, doğum, ekonomik ve diğer

toplumsal konumları yönünden ayrım yapılamaz ve

hiçbir kimseye ayrıcalık tanınamaz.

6. Turkish Legislation Prohibiting Discrimination

TCK

Ayırımcılık

MADDE 122. - (1) Kişiler arasında dil, ırk, renk, cinsiyet, siyasî

düşünce, felsefî inanç, din, mezhep ve benzeri sebeplerle

ayırım yaparak;

a) Bir taşınır veya taşınmaz malın satılmasını, devrini veya bir

hizmetin icrasını veya hizmetten yararlanılmasını engelleyen

veya kişinin işe alınmasını veya alınmamasını yukarıda sayılan

hâllerden birine bağlayan,

b) Besin maddelerini vermeyen veya kamuya arz edilmiş bir

hizmeti yapmayı reddeden,

c) Kişinin olağan bir ekonomik etkinlikte bulunmasını

engelleyen,

Kimse hakkında altı aydan bir yıla kadar hapis veya adlî para

cezası verilir.

• TCK’da yer alan ayrımcılık ile ilgili diğer maddeler: 115,

125,153

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

Let us return to the concept of substantive equality:

“Equality of outcomes is a substantive conception of equality, as it attempts to provide

substance to the concept of equality. Unlike formal equality, which dictates behaviour

through applying rules and procedures consistently, equality of outcomes seeks to

invest a certain moral principle (namely social redistribution) into the application of

equality. This concept of equality manifests itself through a spectrum of policies and

legal mechanisms in various jurisdictions. Reverse discrimination, positive

discrimination, and affirmative action are just a few which have been put forward to

represent this concept. Positive discrimination can be succinctly discerned from positive

action:

(Jarlath, 2007)

Negative and positive duties of the State:

•The distinction between ‘formal’ and ‘substantive’ conceptions of equality can also be

expressed in terms of a distinction between negative and positive obligations to effect

or achieve equality before the law.

•The traditional approach of much equality law has been protecting people from

discrimination, i.e. preventing employers and service-providers from treating people

differently by reference to certain personal characteristics (e.g. sex, ethnicity, national

origin, etc). This prohibition on non-discrimination is a classic instance of a negative

obligation.

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

• By contrast, positive obligations are requirements upon employers

and the like to adopt specific measures to promote access by underrepresented groups, e.g. ‘affirmative action’ in the name of securing

equal opportunities.

• There is a wide range of possible positive measures available, from

offering increased resources for education of under-represented

groups (e.g. scholarships), requiring workplaces to be accessible to

persons with disabilities, to more controversial measures such as

preferential hiring and – most controversially – quotas. In general, it is

consistent with the idea of equality for the state to expend additional

resources to ensure equality of opportunity for persons from underrepresented groups in society. Whether more overt measures

amounting to so called ‘positive discrimination’ are acceptable means

of combating past discrimination is something that continues to be

debated.

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

Affirmative action: Destekleyici edim

Temporary special measure: Geçici özel önlem

Positive measure: Pozitif önlem

From the Review of the implementation of the Bejing Platform Action and the outcome

documents of the special session of the General Assembly entitled ‘Women 2000:

gender equality, development and peace for the twenty-first century”, Report of the

Secretary-General, Economic and Social Council, 6 December 2004:

“337. Almost half of all countries reported on quotas or affirmative action measures and

their positive impact on women’s participation in decision-making. Many countries

adopted different types of measures as an effective way to address gender imbalance.

Temporary special measures, as called for in article 4.1 of the Convention on the

Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, are necessary to accelerate

de facto equality, redress past discrimination against women and give them equal

opportunities with men for decision-making, jobs and education. The most common

forms of quota system are those introduced through constitutional or national

legislation, and those that are adopted voluntarily by political parties. For example,

France introduced a constitutional amendment requiring political parties to include 50

per cent representation of women on their party lists for election; India reserved 33 per

cent of local government seats for women; and Mozambique’s Frelimo Party introduced

a 30 per cent quota on electoral lists. “

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

Marschall v. Land Norhein-Westfalen (ECJ, 1997):

Mr. Marschall was a teacher in Germany who applied for a promoted post. He

was informed that the preference would be to appoint a female candidate as

there were fewer females than males appointed at that level. Mr. Marschall

argued that this was contrary to the EU laws on equality of opportunity

between men and women. The German authorities, however, argued that

the measure was necessary to redress the gender imbalance in employment

at senior levels. Compatibility of the German law with EU law on equality

was queried before the ECJ.

“Even where male and female candidates are equally qualified, male candidates

tend to be promoted in preference to female candidates particularly

because of prejudices and stereotypes concerning the role and capacities of

women in working life and the fear, for example, that women will interrupt

their careers more frequently, that owing to household and family duties

they will be less flexible in their working hours, or that they will be absent

from work more frequently because pregnancy, childbirth and

breastfeeding.” (para. 29)

• http://www.cnnturk.com/2011/turkiye/11/13/c

alisan.kadinlarin.en.buyuk.sorunu.ayrimcilik/63

6561.0/index.html

7. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive measures/(temporary) special

measures

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978)

Facts: The University of California, Davis Medical School reserved 16 spots out of the

100 in any given class for “disadvantaged minorities.” The Respondent, when compared

to students admitted under the special admissions program, had more favorable

objective indicia of performance, while his race was the only distinguishing

characteristic. The Respondent sued, alleging that the special admissions program

denied him equal protection of laws under the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution.

The Court's Decision

A splintered Supreme Court affirmed the judgment ordering Bakke's admission to the

medical school of the University of California at Davis and invalidating the school's

special admissions program. However, the Court did not prohibit the school from

considering race as a factor in future admissions decisions. Justice Lewis Powell, Jr.,

announced the Court's judgment. Four justices agreed with his conclusions as to Bakke

individually, and four other justices agreed with the ruling as to use of race information

in the future.

Justice Powell wrote that “the guarantee of Equal Protection cannot mean one thing

when applied to one individual and something else when applied to a person of another

color.” He did not, however, prohibit schools from considering race as one factor in the

admissions process.

Justice Thurgood Marshall argued that race could properly be considered in an

affirmative action program, a policy of taking positive steps to remedy the effects of

past discrimination. “In light of the sorry history of discrimination and its devastating

impact on the lives of Negroes, bringing the Negro into the mainstream of American life

should be a state interest of the highest order. To fail to do so is to ensure that America

will forever remain a divided society. I do not believe that the Fourteenth Amendment

5. Combatting discrimination through affirmative action/positive

measures/(temporary) special measures

More on the Case

The legal impact of Bakke was reduced by the disagreement among the justices.

Because the Court had no single majority position, the case could not give clear

guidance on the extent to which colleges could consider race as part of an affirmative

action program.

In Texas v. Hopwood, 1996, a federal appeals court found that a University of Texas

affirmative action program violated the rights of white applicants. The law school was

trying to boost enrollment of African Americans and Mexican Americans. The court

assumed that the Bakke decision was no longer legally sound, and explicitly ruled that

“the law school may not use race as a factor in law school admissions.” The court

continued: “A university may properly favor one applicant over another because

of…whether an applicant's parents attended college or the applicant's economic and

social background.…But the key is that race itself cannot be taken into account.” The

Supreme Court refused to review the appeals court decision.

Affirmative action remains a controversial issue in California. In 1996, voters passed the

California Civil Rights Initiative, generally known as “Proposition 209,” which prohibited

all government agencies and institutions from giving preferential treatment to

individuals based on their race or gender. The Supreme Court also refused to hear an

appeal from a decision upholding the constitutionality of the law.

Read more: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978)

http://www.infoplease.com/us/supreme-court/cases/ar32.html#ixzz1gYSGiyy3

“Bugün ırkçılık Avrupa'da ve Kuzey Amerika'da değişik bir düzeyde

ilerliyor. Artık Nazi ve KKK ırkçılığından büyük ölçüde sıyrılmış, daha az

belirgin, daha 'liberal' ve kandan çok kültüre endekslenmiş bir ırkçılık var.

Bugün ırkçılık siyahlar, Araplar veya Hintlilerin aptal ve tamamen iğrenç

varlıklar olduğunu söylemiyor. Tam tersi, gayet normaller, ben onları

seviyorum ve hatta onlar benim arkadaşlarım diyor. Fakat bazı küçük

ayrıntılardan rahatsız olduğunu söylüyor. Mesela müziklerinin gürültülü,

yemeklerinin baharatlı, dillerinin kaba veya çalışma etiklerinin ters

olması günümüz ırkçılık söylemini oluşturuyor. Kültür endeksli bu

söylem, ırkçılığı günlük hayatta çok zor karşı koyulan bir olgu haline

getiriyor. "Müziklerini veya yemeklerini sevmek zorunda değilim"

argümanından "müzikleri çok ilkel" veya "yemek kokuları bizim eve

kadar geliyor" yargısına kolayca geçilebiliyor. Fransa'da eski söylem

ırkçılığıyla tanınan Le Pen'in partisi Ulusal Cephe bile artık bu yeni

söylem ırkçılıktan destek alıyor.... “

“...Aynı şekilde ABD medyası siyahlara, kızılderililere ve birçok göçmen

gruba kültüre dayalı genelden varılan bir sonuçla yaklaşır. "Siyahlar

gettolarda yaşarlar, o ortamda büyümek onları ister istemez saldırgan

yapar ve suça yöneltir" misali bir gerçeklikten yola çıkan realite şovlarda

bütün suçları siyahlar işler. Amerikalı yazar ve yönetmen Michael Moore

bu tür bir söylemi etkili bir şekilde sorgular: "Benim en çok korktuğum

adamlar beyazlardır çünkü evimi soyan, teybimi çalan, babamı işten

atan, maaşını kesen beyaz adamdır" der. Hakikaten düşünün bir,

hayatında hiç siyah birisinden kötülük görmemiş fakat hep beyazların

gazabına uğramış bir Amerikalı gene de siyahların daha tehlikeli

olduğunu düşünür.”

Defne Karaosmanoglu 07.03.2004